A Fierce Foe of Anti-Semitism

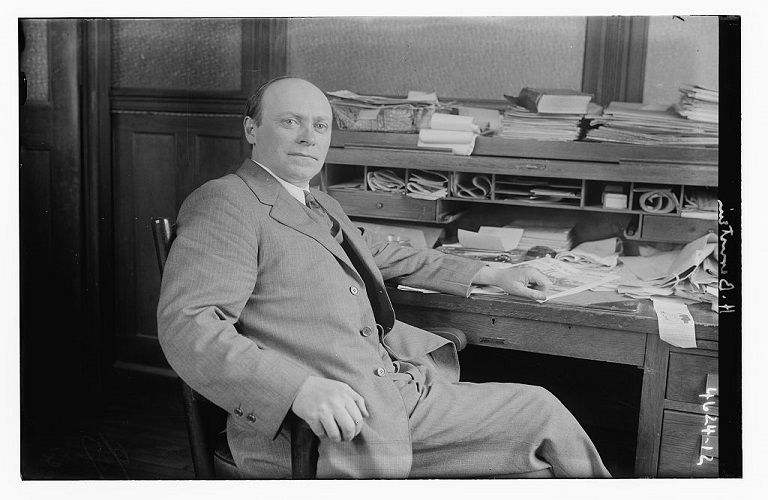

If there were a CAM Hall of Fame, one of the first inductees would have to be a Jewish American writer and diplomat by the name of Herman Bernstein.

Born in 1876 in Lithuania, Bernstein emigrated to the United States with his family at the age of 17. A prolific journalist, he ran Der Tog (“The Day”), a short-lived Yiddish language daily in New York, and edited for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in the Hague and Jewish newspapers in Britain. His travels to Europe as a New York Times correspondent enabled him to chronicle the situation of European Jewry at the time of the First World War. He also covered the Russian Revolution of 1917 for the New York Herald.

His most dramatic scoop was his revelation of telegrams exchanged by two monarchs who were blood relations: Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. In his book on the telegrams, The Willy-Nicky Correspondence (1918), Bernstein wrote of the Kaiser’s bellicosity and manipulation of the Tsar in the years leading up to the war. The book was an early documenting of the misrule of both men—a misrule that included, in Bernstein’s words, “the enslavement of the Jews in German Poland and Lithuania.”

In 1921, while a New York Herald reporter, Bernstein criticized anti-Jewish articles appearing in the Dearborn Independent, a newspaper in Michigan owned by Henry Ford, the automobile pioneer. The articles gave credence to a forged document that had already been discredited, purporting to be evidence of a Jewish conspiracy to rule the world. It was the Tsar’s secret police who were circulating the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” and Ford and other Americans were falling for it. To defeat this pernicious conspiracy theory, the journalist took up his pen. Another Bernstein book, The History of a Lie (1921), was the result.

Politically, Bernstein was a high-profile member of the Democratic Party. But he was impressed by the aid work that Republican Herbert Hoover did in European countries. He became a Hoover supporter (and biographer), and when Hoover won the presidency, Bernstein was appointed U.S. ambassador to Albania.

Serving in that capacity from 1930 to 1933, Herman Bernstein fostered the U.S.-Albanian relationship, and marveled at the thriving Jewish community of Albania, a tolerant Muslim country. He witnessed warm Albanian-Jewish relations at a time when the other European countries were either indifferent to the fate of the Jews or actively hostile. Albania would go on, after Bernstein’s death in 1935, to defy the fascist powers of Europe by refusing to deliver its Jewish population to the Third Reich. Not only was every Jew in this tiny nations protected, but there were many Jewish refugees from Austria, Germany, and Yugoslavia who survived the Nazis by escaping to Albania.

In troubled times, the Albanian-Jewish story is a rare example of ethnic and religious friendship, and the absence of anti-Semitism. And Herman Bernstein is a model of vigilance and energy in defense of the Jewish people, here and around the world.