Europe’s role in Combating Anti-Semitism: Interview with Ms. Katharina von Schnurbein

Anti-Semitism in Europe has risen sharply over the last few months. In France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Greece, and Denmark, to name just a few countries, anti-Semitic violence and vandalism terrorized Jewish communities over the High Holiday period, comprising the holiest days of the Jewish calendar. The European Commission recently made the timely decision to announce a new comprehensive strategy for combatting anti-Semitism, scheduled for 2021.

Ms. Katharina von Schnurbein, the European Commission Coordinator on Combatting Anti-Semitism and Fostering Jewish Life, recently participated in a panel discussion at the Balkans Forum Against Anti-Semitism. This week, CAM spoke to Ms. von Schnurbein to get an inside perspective on European efforts to combat anti-Semitism.

CAM: Ms. von Schnurbein, the European Commission recently announced that it will present a new comprehensive strategy on anti-Semitism, to be launched in 2021. Why, in your view, is a strategy necessary and how will it step up the Commission’s actions compared to its current approach to fighting anti-Semitism?

Anti-Semitism is on the rise in the European Union and beyond. If we look at the latest annual overview on anti-Semitism from the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights we see that thousands of officially recorded incidents take place each year in the EU, and due to underreporting this is only the tip of the iceberg. Terrorist attacks, like on the synagogue in Halle in 2019 and on the kosher supermarket in Paris in 2015, show us that anti-Semitism has returned to Europe in one of its worst forms.

Jewish people need to be safe and feel safe in the EU. Therefore, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has upscaled the fight against anti-Semitism and the support for Jewish life. As anti-Semitism is an international problem that crosses borders, the announced European Strategy will help to strengthen Europe’s response. It will complement and support Member States’ national strategies and action against anti-Semitism, which are currently being developed. Anti-Semitism needs a holistic response – where the European, national and local level work hand in hand.

CAM: What can we expect from the content of the upcoming strategy?

Anti-Semitism comes in many shapes as is reflected in the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism. All forms of anti-Semitism are equally pernicious, no matter what the source is. It will take a holistic approach that takes into account the various policy areas. The EU has different roles. For example, when it comes to legislation to make hate speech and hate crime a Eurocrime, which will allow better prosecution across the EU, the Commission is in the driving seat. The same is true for project funding and certain research. When it is about education, safety, data recording, victim support, training of law enforcement and teachers, we can help Member States with best practices and guidance, rather than they having to reinvent the wheel in each country.

CAM: The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of anti-Semitism has a formal stamp of approval from the EU. Nonetheless, many member states have not adopted the definition. What should be done to encourage all EU member states to adopt the IHRA definition?

It is important to realize that “We can’t fight it if we can’t define it”. The non-legally binding IHRA working definition of anti-Semitism has become the benchmark to address all forms of anti-Semitism. The examples help to identify what is anti-Semitic violence and speech, and what is not. So far, 18 EU Member States have adopted or endorsed the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism, and in the 2018 Council Declaration on the fight against anti-Semitism, those countries that have not done so yet are encouraged to adopt it. Therefore, we expect all Member States to adopt the IHRA definition in the near future. Nevertheless, adoption alone is not enough – it needs to be used, for instance in training for law enforcement authorities, teachers, or government decision-makers. To facilitate the use, the Commission will issue in December, together with IHRA, a Guidance Manual with best practices from various countries. The definition can also be adopted by local authorities like cities, civil society associations, universities, and many other types of organizations. For the Commission, I co-signed the recent letter by Lord John Mann to encourage professional league football clubs to adopt the definition and lead by example in the fight against anti-Semitism and racism.

CAM: We have seen anti-Semitic violence and vandalism become commonplace over the last few months. This includes attacks outside synagogues, graveyard vandalism, and tagging kosher stores and places of worship, as well as public places. What is driving this form of anti-Semitism?

In fact, anti-Semitism in this form has been on the rise since the early 2000s. We have witnessed a rise of hate speech and anti-Semitic incidents by the extreme-right movement, the extreme-left, and radical Islamists. This rise has many causes, ranging from the erosion of the post-Holocaust taboo on anti-Semitism or the belief in conspiracy ideologies, caused by a lack of trust in governments or the age-old trope of scapegoating the Jews.

The internet and social media allow for spreading and coordinating hatred and hate full actions faster than ever. The spiral has further accelerated during COVID-19 as we witnessed a significant increase of anti-Semitic hate speech and conspiracy. As we face recession, a major challenge will be how we prevent any minority, Jews or others, from being blamed for the difficulties that people are going through. In times of crisis, it is even more crucial to guarantee the fundamental rights of all. Our strategy will therefore also address the consequences of the Covid-19 crisis.

CAM: We have also seen a rise in online anti-Semitism, specifically conspiracy theories related to the Jewish people. In Europe, the conspiracy theory known as “QAnon” is growing rapidly in countries such as France, Germany, and Italy. What is the cause of this and what can be done to combat online disinformation?

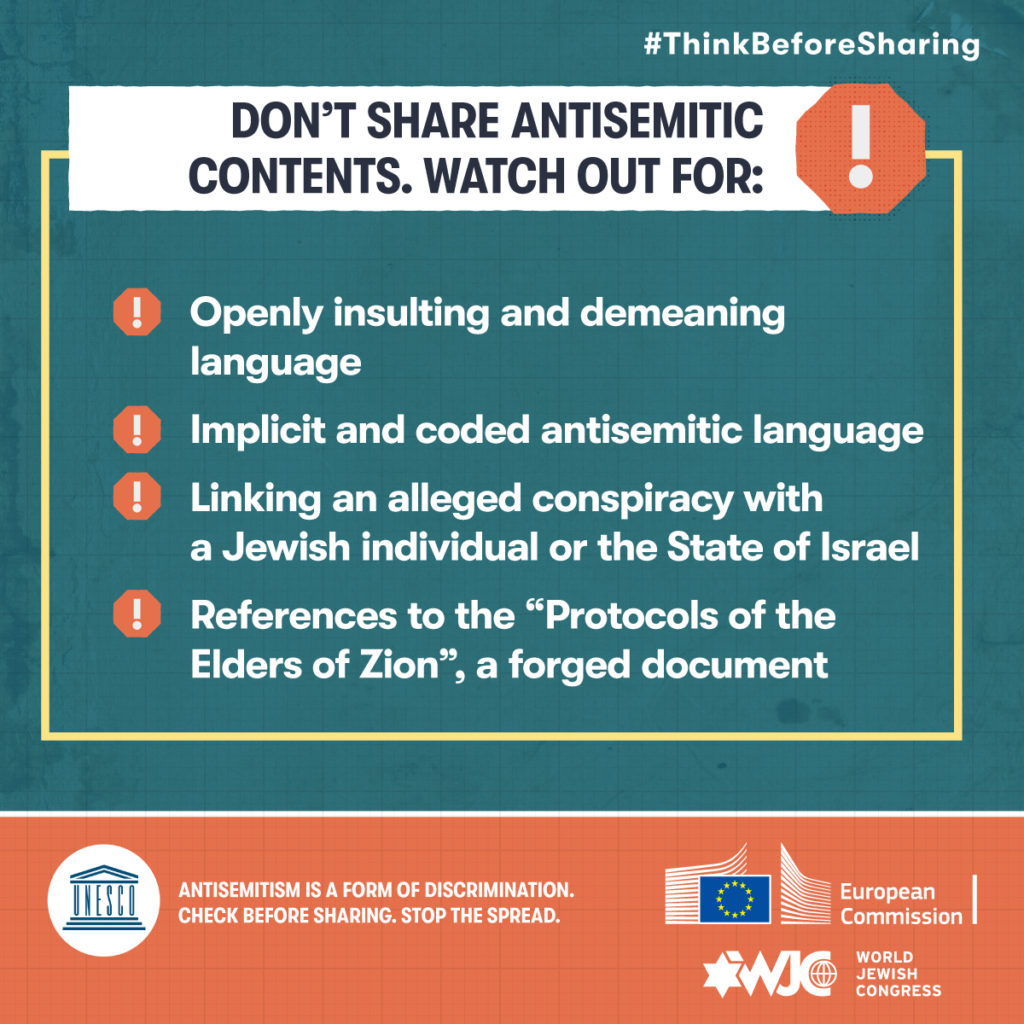

A crisis like this can increase the need for people to believe in ideologies that help them explain developments in society and that put the blame for these developments on others, be it the elite, the so-called ‘deep state’, or a minority, like the Jewish people. The internet and the bubbles created by algorithms accelerate the process. Together with UNESCO, the Commission launched the media campaign #ThinkBeforeSharing on Twitter in July to address and pre-empt the spreading of conspiracy myths. In 2016, the Commission concluded a Code of Conduct with major social media platforms on the quick removal of illegal hate speech online. It has helped to develop effective systems to faster review hate speech notices by users, and remove content when necessary. It provides mechanisms of cooperation between IT Companies and civil society organizations, including Jewish organizations. The proactive decision of social media platforms to take down illegal content such as Holocaust denial is another concrete step.

However, we need to go further. We have seen in the attack on the synagogues in Halle or Pittsburgh, but also the kosher store in Paris or the Jewish Museum in Brussels, that the road from conspiracy ideology to hate crime is short. As part of European counter terrorism measures, intelligence organizations have started to pool their forces better. In 2018, the Commission proposed the removal of terrorist content online within one hour – this legislation is stuck in the European Parliament and needs to be adopted urgently. Secondly, with the soon to be proposed Digital Services Act the Commission aims to harmonize a clear set of due-diligence obligations for online platforms, including notice-and-action procedures for illegal content, redress mechanisms, accountability measures, and cooperation obligations with public authorities. The Act would also ensure greater transparency on how platforms moderate content, on advertising, and on algorithmic processes.

Nonetheless, combating hate speech and disinformation online will not work without a policy that also combats anti-Semitism offline, or in the real world. People find anti-Semitic content online, but we will also need to address why they tend to believe it and feel attracted to it in the first place. That is why a holistic approach to combat anti-Semitism is so important.

CAM: Anti-Semitism is too often seen as a problem for Jewish groups to deal with, rather than a societal problem that we must face together. What can be done to encourage people around Europe to ally with Jewish communities and stand up against anti-Semitism?

Anti-Semitism is not a Jewish problem, but it targets Jews above all. It is not just a local problem. It is a European and a global issue. The hate that begins with Jews never ends with Jews. Anti-Semitism, the world’s oldest hatred, is a threat to the fabric of democracy. This plague is contrary to our European way of life, which is based on the values of human rights, equality, freedom, respect of human dignity, regardless of identity, origin or belief.

With our policies and project funding, we promote building strong relationships between religious and cultural groups, to combat anti-Semitism and religious extremism. We support organizing coalitions between faith and other groups, to forge a united front against hate.

We need to focus on youth, teach history, and show that living in a diverse society where everyone has a place, is not a threat, but an asset. This is even more important today as we are moving into a new era, one in which direct witnesses of the Holocaust are no longer with us. We must ensure and renew the keeping of this memory.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.