|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Bondi Beach was part of Dionne Taylor’s routine. She walked there several times a week, met friends there for coffee. It was familiar, safe — until it wasn’t.

When terrorists struck a Hanukkah menorah-lighting ceremony at Bondi Beach on on Sunday, Taylor was not there. Friends of hers were. Some were shot. Others were not. Messages flooded WhatsApp groups as fragments of information spread faster than confirmation. Gradually, the picture sharpened into something real and devastating: gunfire at a Jewish gathering, people murdered and wounded — people she knew, children she knew.

Taylor is the communications manager for the Australian Israel & Jewish Affairs Council (AIJAC). She lives in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, about a ten-minute walk from Bondi Beach, home to a large Jewish population.

The news reached her while she was at another Hanukkah gathering. She left soon after and went home. For hours, helicopters circled overhead and sirens raced through the streets as emergency crews transported the wounded to hospitals across the city — spread out, she said, because the system could not handle a mass-casualty terror incident.

“This is the first attack where Jews have been murdered in Australia,” Taylor said. “We are shocked, but we are not surprised.”

This interview took place the day after the massacre.

You live just minutes from the shoreline and heard the chaos unfold in real time. Can you take us back to that moment — what you heard, what you immediately understood, and when it became clear this was a targeted attack on a Jewish gathering?

“Bondi Beach is about a 10-minute walk from where I live,” she said. “It’s a very populated Jewish community. Bondi Beach is not only a tourist destination—it’s our backyard.”

She wasn’t there when the attack unfolded. “Last night I was not there when this unfolded,” Taylor said. “I have friends who were there… some have been shot, some have not been shot.”

The targeting was immediately clear based on what she already knew was happening that night. “We knew there was a Hanukkah festival that was happening,” she said. “It was widely publicized among the Jewish WhatsApp groups that I’m in.” She also knew “of someone who was having a bar mitzvah there.”

“The minute that I heard that,” Taylor said, “I thought, oh my God — this is a direct attack.”

As information spread unevenly, she tried to keep one rule intact. “Unless this information is verified, I don’t take it as truth,” she said. “Everyone’s shouting out, apparently this, apparently that… and I’m like, guys, stop — unless it’s true, don’t go there.”

But the danger was already real. “Very quickly we learned that there was a gunman,” she said. “Shots were fired.” Then came confirmation that couldn’t be dismissed. “We started to hear that people that we know were shot,” Taylor said. “Children of people that we know were shot as well.”

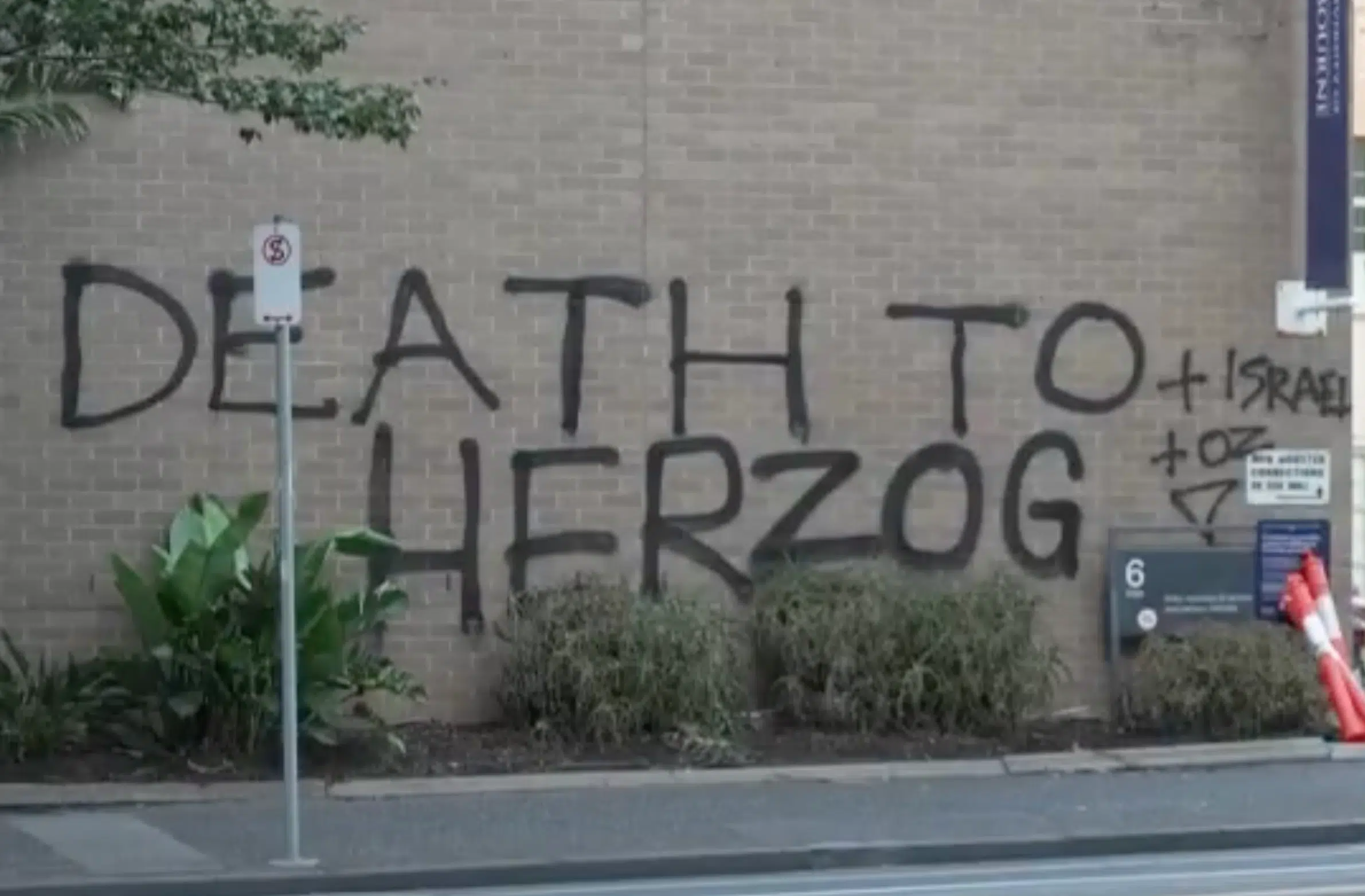

The escalation, Taylor added, had been visible for months. “We’ve seen the hatred towards the Jews fester and grow from hate speech to graffiti to marches to arson attacks — and now to murder,” she said.

AIJAC has warned Australian authorities about rising antisemitism since October 7th. What responses did you receive before the attack?

“We’ve received multiple empty, pathetic calls for solidarity and sadness,” Taylor said. “‘Antisemitism has no place in Australian society.’ ‘We must repair the social cohesion of our community in Australia.’ ‘We must stand for all Australians,’ blah, blah, blah.”

“Basically every government official was given the same three key messages,” Taylor said, “that actually say nothing and do nothing.”

She pointed to moments she believed emboldened what came next. “On October 9, 2023 — just two days after October 7th — at the Opera House steps,” she recalled, “the pro-Palestinian jihadists were standing there calling to gas the Jews and the police just stood there idly doing absolutely nothing.”

After that, she said, “our community security warned us not to leave our houses because that was not safe for us to be in public spaces.”

Taylor cited the Sydney Harbour Bridge anti-Israel march earlier this year. “About 300,000 people walked across the bridge,” she said. What stood out, she added, was what was absent and what wasn’t. “Hardly any Australian flags were there. There were Palestinian flags, lots of Palestinian flags, Hamas flags, the Ayatollah — it was endless.”

“That was horrifying for the Australian Jewish community,” she said. “Gut-wrenching. Heartbreaking. A stab in the heart.”

Then came Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s speech at the United Nations in September. “Just six weeks later, Anthony Albanese stood in front of the UN and recognised the Palestinian state,” Taylor said. “That was it. That’s the nail in the coffin.”

Since then, antisemitic incidents have ranged “from micro through to macro,” she said. What worries her now is what comes next. “I’ve spoken to people in high places,” Taylor said, “who have told me they don’t think this is the end. They think it’s going to be worse.”

Iran has spent years exporting jihadist ideology and funding terror proxies. How are those networks influencing threats in Australia, and why can leaders no longer downplay this danger?

“It has been a real and urgent threat for the last two years,” she said. “It’s just been ignored and now they’re finally paying attention.”

She pointed to prior attacks in Melbourne. “When there were fire bombings at synagogues, childcare centers, homes, kosher restaurants,” Taylor said, “they finally uncovered that there were connections to the IRGC [Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps] and they got proxies to do the dirty work for them.” Those links were traced with Israeli intelligence. “They were able to make the links back to the IRGC,” she noted.

Taylor highlighted one decision she believes mattered. “Probably the first and only commendable thing the government did,” Taylor said, “was immediately closing the Iranian embassy.”

For years, she said, Iran was treated as distant and irrelevant. “When you live so far away and if the Middle East just does not concern you,” she said, “why would they care?”

“That’s changed now,” Taylor said. “Now it affects them. Now they understand.”

She stressed the generational cost. “As a child, the only way that I learned about antisemitism was through books and museums,” she said. “My children are learning it through lived experience.”

One moment at home made the impact on her children unmistakable. With non-Jewish guests due to stay in their house, her daughter asked whether they should remove visible signs of their Jewish identity. “She said, ‘Mommy, should we take down all our Jewish things while they stay?’” Taylor remembered. “She goes, ‘but what if they’re terrorists?’”

Her response was immediate. “I said, no… there’s nothing wrong with that. You have to be proud that you’re Jewish. I’m not taking anything down. Absolutely not.”

After October 7th, her daughter also asked to hide Jewish identifiers at school. “She wanted to take off her Magen David,” Taylor said. “I said, no. You wear that proudly.”

When people defend slogans like “Globalize the Intifada” and other rhetoric demonizing Jews or Israel as free speech, what responsibility do they bear when that language helps create the conditions for violence?

“This has happened on university campuses,” Taylor said. “It’s happened on the streets.” In Melbourne, she added, “the streets are closed every weekend.” The rhetoric is reaching children too. “Children are chanting these things,” Taylor said, “like they’ve been indoctrinated from a young age.”

“When these marches don’t get shut down, and when they happen in front of synagogues,” she said, “it spreads. It becomes normal.”

Taylor pointed directly to one slogan. “They wanted to ‘Globalize the Intifada,'” Taylor said. “Here you go. This is what ‘Globalizing the Intifada’ looks like.”

“It’s thousands of people fleeing for their life,” she said, “while gunmen are firing from vantage points.”

“That’s what ‘Globalizing the Intifada’ is.”

After the Bondi Beach attack, what must national and local leaders — and the Australian public — acknowledge about antisemitism and jihadist violence, and what actions must they take now to prevent this from happening again?

“There are a lot of concrete steps,” she said, starting with enforcement. “Starting with the rule book that Jillian Segal, the envoy for combating antisemitism, has prepared and shared with the government. They’ve taken it into consideration but not enforced it.”

“We need the government and the police to start using the laws they’ve established,” Taylor said. “And if those laws are too weak, they need to come up with new laws and enforce them immediately.”

Taylor also questioned the police response during the attack. “There were police there last night,” she said, “who were down on the ground and did not fire a weapon.” She repeated the timing. “For nine minutes, they did not do anything.”

When told police may have avoided firing in a public space, she rejected that explanation. “That is rubbish,” she said, pointing to a past stabbing attack at a Bondi Junction shopping center as evidence that police could act decisively when needed. “The police were there and one shot — they neutralized the killer.”

“I think that perhaps the police froze,” she said. “They’re human — but where was the protection?”

Still, Taylor believes something may have shifted. The day after the attack, she went to Bondi Beach. “What overwhelmed me,” she said, “was how many non-Jewish people were there — crying.”

“We had rabbis there,” she said. “We had Christian clergy standing with us.”

She received messages from non-Jewish acquaintances. “I’m grateful,” Taylor said. “But I keep thinking — where were you after October 7th?”

Her conclusion was blunt. “It’s not just a Jewish problem,” Taylor said. “It’s a societal problem.”