Rabbi Andrew Baker: ‘We Are Now Waking Up to Something that European Jews Have Addressed for a Number of Years’

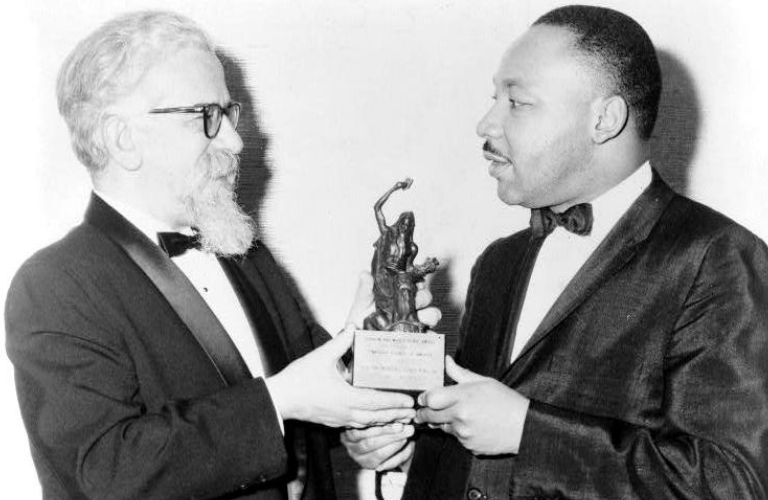

Rabbi Andrew Baker is director of International Jewish Affairs at the American Jewish Committee (AJC), which he joined in 1979, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Personal Representative on Combating anti-Semitism, appointed by the Austrian OSCE Chairmanship. Rabbi Baker has extensive experience promoting tolerance in Europe as part of his role with AJC. To mark International Holocaust Memorial Day on January 27, Tamara Berens at CAM spoke with Rabbi Baker about his crucial work in drafting the Working Definition of anti-Semitism and developing relations with government institutions across Europe to combat the issue.

CAM: Why is it important for governments to define anti-Semitism?

In 2001 and 2002 we were seeing a real surge in anti-Semitic incidents with Jewish targets in Western Europe. There was a belief that the attacks were political in motivation, occurring at a time where the peace process in the Middle East broke down. Governments were dismissing these incidents as political issues rather than as anti-Semitic.

In some cases, we are not only talking about incidents of violence but also verbal harassments. Governments of those states didn’t see it and there was no vehicle to collect and identify incidents: governments themselves weren’t reporting them. It was as if they never took place. But these attacks became so widespread that it became impossible to ignore them.

That was when we saw the first attempts to deal with them. The European Monetary Center (EUMC) conducting its first study of anti-Semitism in Europe and had its first conference on anti-Semitism in 2003. They recognized that over half of their monitors had no definition to use when trying to record or identify anti-Semitism. There were no two definitions that were the same. Few governments were collecting even general hate crime records – even less so those that were anti-Semitic

If you can’t identify and define anti-Semitism, then how can you deal with it?That was one of the essential truths that lead many of us to say: “we need now to focus precisely on this.”

We all understood even at the time that traditional forms of anti-Semitism presented themselves in a variety of ways, including new forms of anti-Semitism related to the state of Israel. We needed a definition of anti-Semitism that would be largely agreed upon by communities, governments, and others.

CAM: When drafting the Working Definition of Anti-Semitism, did you draw from existing definitions of racism in Europe?

The jumping off point was the EUMC report: a recognition by the director of the EUMC that lacking a comprehensive definition of anti-Semitism really hindered their work. I proposed we would try and draw on experts in the field who were collecting historical information on the problem and more recently addressing the issue to see if we could come up with a definition that all of us would agree on.

We were trying to bring forward in one place the various ways in which anti-Semitism has presented itself. Some scholars say it’s a kind of shape-shifting phenomenon. People would understand anti-Semitism as an expression of hatred towards Jews, but fewer would recognize the world of conspiracies about Jews. Anti-Semitism can exist even where Jews are not present. Those who were promoting Holocaust denial were promoting anti-Semitism itself.

We recognized we needed to offer some examples of anti-Semitism as it related to Israel. Jews were in various places a target for Israel and that needed to be called out.

In some places, people may have thought by replacing “Jew” with “Zionist” you could take an anti-Semitic statement and somehow believe it could become acceptable.

The more controversial of points here was how to explain and identify among these examples the ways in which Israel itself could be attacked or set up that would be a manifestation of anti-Semitism all by itself. In other words, when Israel’s very right to exist is called into question.

When the activities of the state of Israel are equated to the Nazis and Israel is held to a standard that no other country is expected to meet, these could be examples of anti-Semitism.

There was an exchange of various formulas and wordings among an ad-hoc group of experts and a lengthy negotiation with EUMC staff and directors that ultimately came to be known as the Working Definition.

The formal use of the definition here [in the United States] has largely focused on activities on American college campuses. Not to digress too much, but we have under the Civil Rights act of 1964 the ability for the government to play a role and address the presence of anti-Semitism on campuses. It means that if, for example, there is a pattern of discrimination or a hostile environment created on these campuses directed towards minorities whether they be African-American or Jews, there can be penalties applied.

We’ve had now for several years through the Department of Education and the presidential executive order of December 2019 the Working Definition – known also as the IHRA definition – considered when making a determination.

CAM: What would you say to those who argue that the Working Definition of Anti-Semitism contravenes free speech?

Much of the debate says this is a tool to prevent free speech, either by directly squelching speech or by causing a chilling effect and intimidating people from saying certain things. In America very ugly, racist, and homophobic speech is still protected speech. In the context of college campuses examining that speech does matter.

My response would be this: the definition is a tool. It’s an important educational tool for people to really understand anti-Semitism in all its forms. But any tool can be misused. If it is simply put into a kind of speech code that would be an absolute tool: “you can say this, you can’t say that,” that would be a misuse of the definition.

CAM: What should be done to encourage all European states to adopt and implement the definition?

At the time I don’t think anyone imagined the goal was a formal adoption by govts or by international institutions. When it was presented as a “Working Definition” it meant just that.

The first uses for it were ad hoc. It found its way into training materials for police cadets in the U.K. and in training programs for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It gained traction in the U.S. Congress which in 2004 adopted a legislation that became a tool for the State Department looking at anti-Semitism worldwide.

Ultimately European institutions began to recognize the importance of something more systematic to recognize anti-Semitism, including the creation of an E.U envoy for anti-Semitism, Katharina von Schnurbein.

Fast forward and it has been formally endorsed and recommended by various associations of the European Council and is now the subject of formal working groups on anti-Semitism that bring together all European member states

In an ironic way the contentious debate [surrounding the definition] serves a positive purpose. It has elevated this definition in the period where this became sensitive under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership [of the British Labour party.] In almost every news report on efforts to use the definition it was referred to as authoritative. It sort of become the definition and gained international acceptance and consensus.

CAM: Do you think American Jews hold misconceptions about anti-Semitism in Europe?

I started my involvement internationally as the American Jewish Committee (AJC)’s European director. I’ve been very much involved for 30 years in Jewish communities. None of us paid much attention to the problem of anti-Semitism in the 1990s. There was a more optimistic feeling about where Europe was; the enthusiasm about Eastern European communities being revived. For most of us it was a matter of thinking anti-Semitism shouldn’t be ignored, but the mentions of a the problems were “well, we had elements of anti-Semitism coming from the right, instances of Holocaust denial,” but certainly anti-Semitism related to Israel wasn’t there.

The sense that in day to day life Jews were confronting harassment was literally not there. European leaders were not seeing this. They were not listening to their Jewish community leaders

It was only when European leaders began listening to Americans that they had to recognize the problem.

My own discussions with Javier Solana, the former Foreign Minister of the European Union went something like this: he said to me, “I don’t see it.” It wasn’t a rejection, it was a suggestion. “Help me see it.” It led him, a year later, to be a pretty strong voice acknowledging anti-Semitism and trying to address it.

U.S. Senators were heard directly and walked into the Elysee Palace. Literally if not that day then that week, the French president announced a special task force to look at the problem.

Coming more into the present times, many American Jews have felt that anti-Semitism is largely a problem elsewhere. Anti-Semitism meaning you need to be fearful and hide your Jewish identity in public. The idea is “we have our problems of anti-Semitism, but not in that context.”

In America, we can be unselfconsciously Jewish. America is a civic identity, everyone has origins from somewhere with a hyphenated identity. In that sense, there is a sense of place in America that Jews in other countries really don’t have.

However, the largest percentage of attacks against religion reported by the FBI are against the Jews. The American Jewish sense of comfort has also clearly diminished with the number of violent attacks recently. We are now waking up to something that European Jews have addressed for a number of years: the need to be focused on physical security.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.