|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Mayor Lorenzo Rodríguez leads Castrillo de Judíos, a small town in northern Spain whose Jewish roots stretch back nearly a thousand years.

Established in 1035, the town originally bore the name Castrillo Mota de Judíos, which historians translate as “Jews’ Hill Camp.” In 1627, amid a climate of religious persecution, authorities changed the name to Castrillo Matajudíos, translated as “Jew-killer Camp,” a hostile and antisemitic distortion introduced in the wake of Spain’s infamous expulsion of its Jewish population in 1492 during the Inquisition.

Nearly four centuries passed before the village finally had the chance to correct this injustice. Under Rodriguez’s leadership, residents voted in a 2014 public referendum to restore the town’s historic name. The municipality carried out that decision the following year, restoring Castrillo de Judíos and reaffirming its connection to the Jewish community that founded the village.

Today, Castrillo de Judíos sets a standard for principled local leadership by choosing accuracy over distortion, dignity over hostility, and memory over silence. Despite facing antisemitic vandalism, threats, and political resistance, the village continues to invest in archaeological research, educational programs, and international partnerships that strengthen historical understanding.

At the 2025 European Mayors Summit Against Antisemitism in Paris, France, last month, the Combat Antisemitism Movement (CAM) honored Mayor Rodríguez for his outstanding leadership and moral courage in fighting antisemitism.

In an interview with CAM, which can be read below, he reflects on the lessons of the referendum, the challenges his community has faced, and the responsibilities European leaders must fulfill at a time of rising antisemitism.

You led the historic effort to replace a medieval antisemitic name with one that honors your village’s Jewish origins. What core principle guided you through that process, and how much opposition did you face?

“When we decided, through a referendum, to recover the historic name of our municipality, that was when the harassment and confrontation began,” Rodríguez said. The backlash came entirely from outside the village. “It came from people outside the village who did not want us to reclaim our past.”

Despite the pressure, the community did not waver. “Our community maintained its decision with the same strength with which it has always defended its identity, from the heart and with deep conviction,” he said. That commitment held firm. “No opposition has been able, or will ever be able, to impose itself.”

For Rodríguez, restoring the name Castrillo de Judíos was both a historical correction and a moral obligation. “Recovering the name Castrillo de Judíos not only honored the Jewish founders who established the village in 1035, but also reaffirmed the dignity and memory of a people who know who they are and where they come from,” he noted.

Castrillo de Judíos is now seen as a model for confronting antisemitism at the local level. What practical guidance would you offer other mayors who want to recover or acknowledge their towns’ Jewish histories?

Rodríguez explained his view clearly. “My advice to any municipality that wants to recover its Jewish past is actually very simple,” he said. “You must feel what you are doing from the heart and act with the deep conviction that it is the right thing.”

He emphasized that this work demanded more than administrative action. Rodríguez put it clearly: “Acknowledging Jewish history is not bureaucracy. It is a moral responsibility.” Progress requires steadiness and patience. “You have to advance with a firm step, knowing that the path will not be easy, but that it can be traveled step by step,” he added.

Rodríguez encouraged leaders to respect all perspectives while staying grounded in truth. “It must be done with respect toward all viewpoints and with a clear goal,” he said. “That goal is recovering historical truth and dignifying the past of the municipality.”

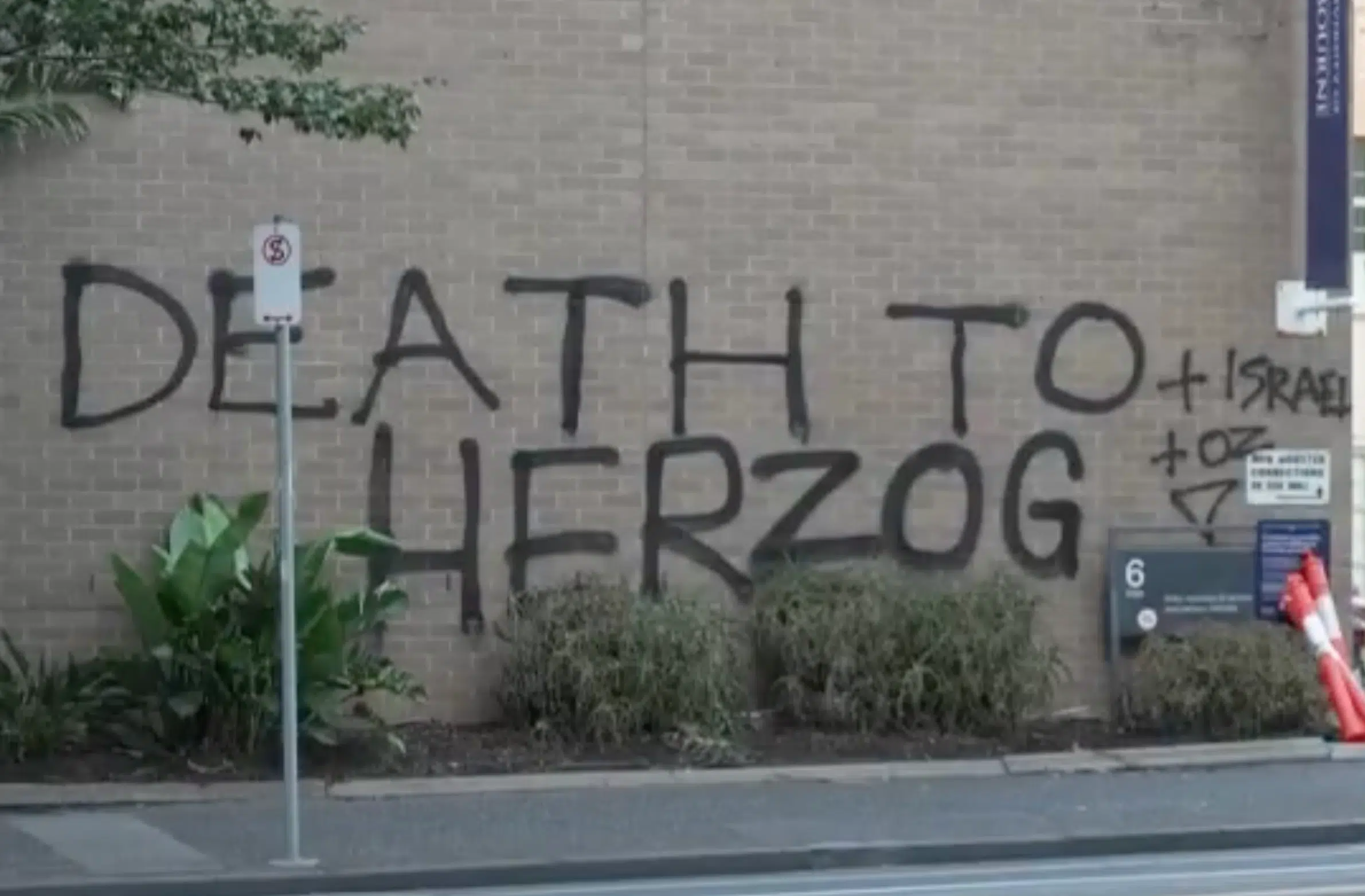

Your village has faced repeated antisemitic vandalism and threats. How have Spanish authorities responded, and what improvements are needed to protect Jewish heritage more effectively?

“After enduring more than a dozen acts of vandalism, bomb threats, and personal threats, the response from the Spanish authorities has unfortunately been one of complete neglect,” Rodríguez said. Despite the repeated attacks, officials blocked the village from taking even basic security measures. “The municipality could not take steps to protect itself, such as installing security cameras,” he explained. “We filed half a dozen complaints in court, and none of them produced any result.”

For him, the issue reflects a broader national problem. “Unfortunately, we have a government that, instead of protecting and promoting coexistence, encourages hatred toward the Jewish people,” he said.

Effective action requires substance, not declarations. “To fight antisemitism, we need culture, education, and knowledge of the history of every municipality,” Rodríguez stressed. “What we do not need are leaders who fuel hostility.”

You have invested in archaeological excavations and educational projects. What remains have you uncovered, and how do you hope this work will affect younger generations and help curb antisemitism today?

“We have been carrying out archaeological excavations for several years in the area where the Jewish community settled in 1035 and remained until the expulsion in 1492,” Rodríguez pointed out. These excavations have revealed tangible pieces of Jewish communal life. “We are restoring the original streets of the settlement, the remains of buildings that once belonged to the community, which housed between five hundred and a thousand people, as well as the burial sites of its members,” he said.

The village’s location strengthens the importance of this work. “It is important to note that the Camino de Santiago passes directly through Castrillo,” Rodríguez said. “That makes our municipality a strategic point of historical and cultural interest for visitors from all over the world.”

One major achievement is a new memory center. “The first Sephardic memory center of the municipality has already been built,” Rodríguez said. “It is a space dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of the Jewish community of Castrillo.”

Funding remains a challenge. “Nearly all of the economic effort falls on the town hall and its staff,” he explained. “And it is not enough to fully develop the archaeological potential or make it accessible to visitors in the way it deserves.”

“We need people who are interested in supporting and collaborating in this work,” Rodríguez said. “Only together can we protect, share, and elevate the history of our Jewish community.”

Your twinning with Kfar Vradim and your relationships in Israel give you a unique perspective on Jewish life today. Since October 7th, what have these conversations taught you about the threats Jews face globally, and what should European leaders learn from them?

“My partnership with Kfar Vradim and my ties with Israel have shown me that Jews continue to face very real threats across the world,” Rodríguez said. The aftermath of October 7th made this reality even clearer. “Since October 7, I have learned that the security and dignity of Jewish communities require firm action.”

He urged European leaders to understand the lessons of this moment. “Leaders in Europe and around the world need to understand that peace cannot be built on resentment or sectarianism,” he said. Ignoring hatred leads to predictable outcomes. “As history shows, humanity cannot stumble twice over the same stone,” he continued.

For Rodríguez, responsible leadership begins with education and historical understanding. “Politics must give way to culture and history as tools to educate, to prevent hatred, and to protect the present and future of Jewish communities,” he said.

As antisemitism rises across Europe, what advice would you give Jewish communities?

“My advice to Jewish communities in Europe is to stay united, stay firm, and stay conscious of your history,” Rodríguez said. “It is essential not to normalize antisemitism and to denounce every form of hatred, whether verbal, physical, or institutional.”

He believes education and memory remain essential tools for resilience. “We must strengthen education and historical memory, inside and outside the community,” he said. Young people, he added, must learn what coexistence truly means. “We must show them that living together means respecting every belief and every way of life,” he said.

Rodríguez invoked the famous saying that “Evil triumphs when good people do nothing.” From that idea, he said, communities must draw strength. “We must defend, from the heart, who we are,” he added.

Rodríguez also called for accountability from political leaders. “We must demand responsibility from those leaders who generate hate to hide their own failures, because true leadership must promote dialogue, respect, and coexistence,” he implored.

Rodríguez closed on a hopeful note. “This is why we need more municipalities like Castrillo de Judíos that speak loudly and clearly against antisemitism,” he said. “We hope that all committed people can help ensure that what we are doing in Castrillo continues, preserving its history and memory.”

Mayor Rodríguez can be contacted at: aytocastrillomotadejudios@