|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

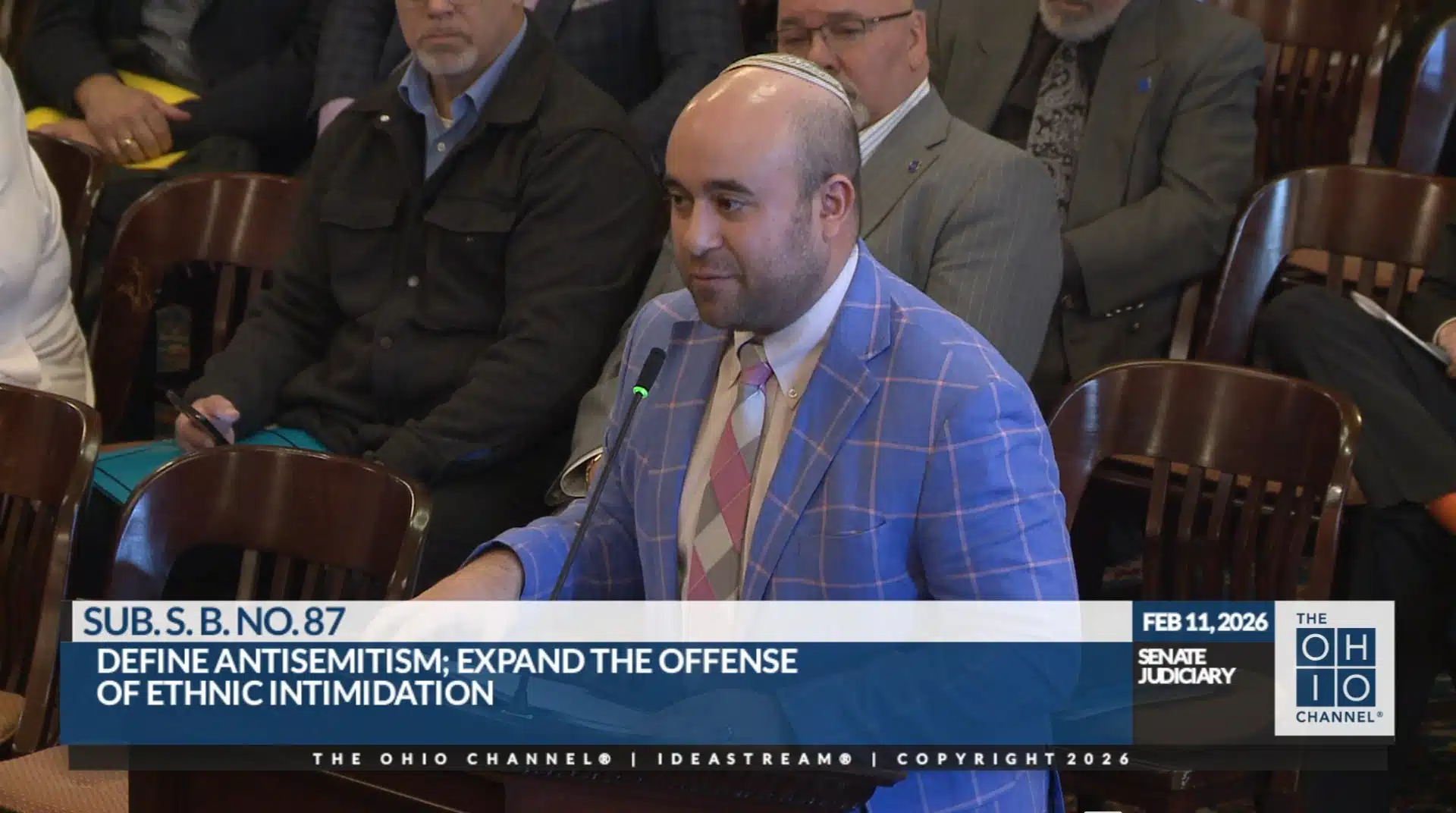

Sheikh Mahammad Mehdizade — European Director of the Global Imams Council — has emerged as a courageous voice in speaking up against antisemitism and religious extremism in Europe.

Originally from Azerbaijan, Mehdizade works to foster interfaith understanding and counter radical ideologies through education, leadership, and action. Last month, he was among the leading Muslim figures to participate in the Combat Antisemitism Movement (CAM)-organized 2025 European Mayors Summit Against Antisemitism, in Paris, France, where he called for honest, sustained engagement between Muslim and Jewish communities.

In this exclusive interview, Mehdizade offers his thoughts and insights on the importance of history, interfaith cooperation, and mutual responsibility in combating antisemitism and building lasting coexistence.

What personal experiences or beliefs compel you, as a Muslim cleric, to stand publicly with the Jewish people, especially amid rising antisemitism in Europe and beyond?

“Islam does not permit antisemitism, extremism or racism. It is impossible,” Mehdizade said. For him, confronting hatred is a core obligation of religious leadership. “We as Muslims cannot be against Jews,” he emphasized.

Mehdizade explained that antisemitism contradicted Islamic teachings, which honor all prophets, including Moses. “We believe in Moses,” he said. “We believe in the prophets before Muhammad. So how can Muslims be antisemitic? It means something has gone very wrong.”

Mehdizade spoke of a time more than a hundred years ago when Jews, Muslims and Christians lived together in peaceful coexistence. “No one used to ask ‘Are you Jewish? Are you Muslim?’ We lived as neighbors. We respected each other,” he recalled. “But now, just a small difference and people ask ‘Are you Jewish? Are you Zionist?’ That did not exist before.”

He was clear in his denunciation of terror groups acting in the name of Islam. “As a Shia imam, I can say clearly that attacking Israel is not allowed in our religion. In Shia law, we do not have jihad like this, unlike Sunni. When they commit violence in the name of Islam they are not just attacking Israelis. They are attacking Islam itself.”

As the Global Imams Council’s European director, you’ve seen how imported conflicts and extremist rhetoric have fueled rising antisemitism. What concrete steps must Muslim leaders and institutions in France take now to push back and protect Jewish communities?

This work, Mehdizade said, must start with education. “If someone understands Islam, they will never be antisemitic,” he asserted. “Islam is not antisemitic.” He stressed that a true grasp of Islamic teachings shielded believers from hatred not only toward Jews but from all “toxic ideologies.” Violence committed in the name of Islam, he continued, was a betrayal of the faith. “If someone says, ‘I am Muslim,’ and they hate Jews or attack them, that is not Islam,” he noted. “That is terrorism.”

Conflicts and disagreements, he said, must be handled through dialogue, not through violence or incitement. “If you have a political issue or a religious question, there are ways to discuss it,” he said. “Killing someone just because they are Jewish is not religion. That is not humanity.”

Mehdizade pointed to a recent protest in Paris where Senegalese Muslims prayed in the street. While prayer was sacred, he opposed using it in ways that disrupted others. “There is a time and a place for everything,” he said. “If your prayer interferes with another religion or community, it is not right.”

For Mehdizade, the role of faith leaders is to lead with responsibility and set moral boundaries. “If your first step is to attack someone because they are Jewish, you are not a believer,” he stated. “You are just a terrorist.”

The Global Imams Council adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) Working Definition of Antisemitism, which distinguishes antisemitism from legitimate criticism of Israel. Why was this definition important to you personally? And how do you respond to those who challenge or misrepresent it?

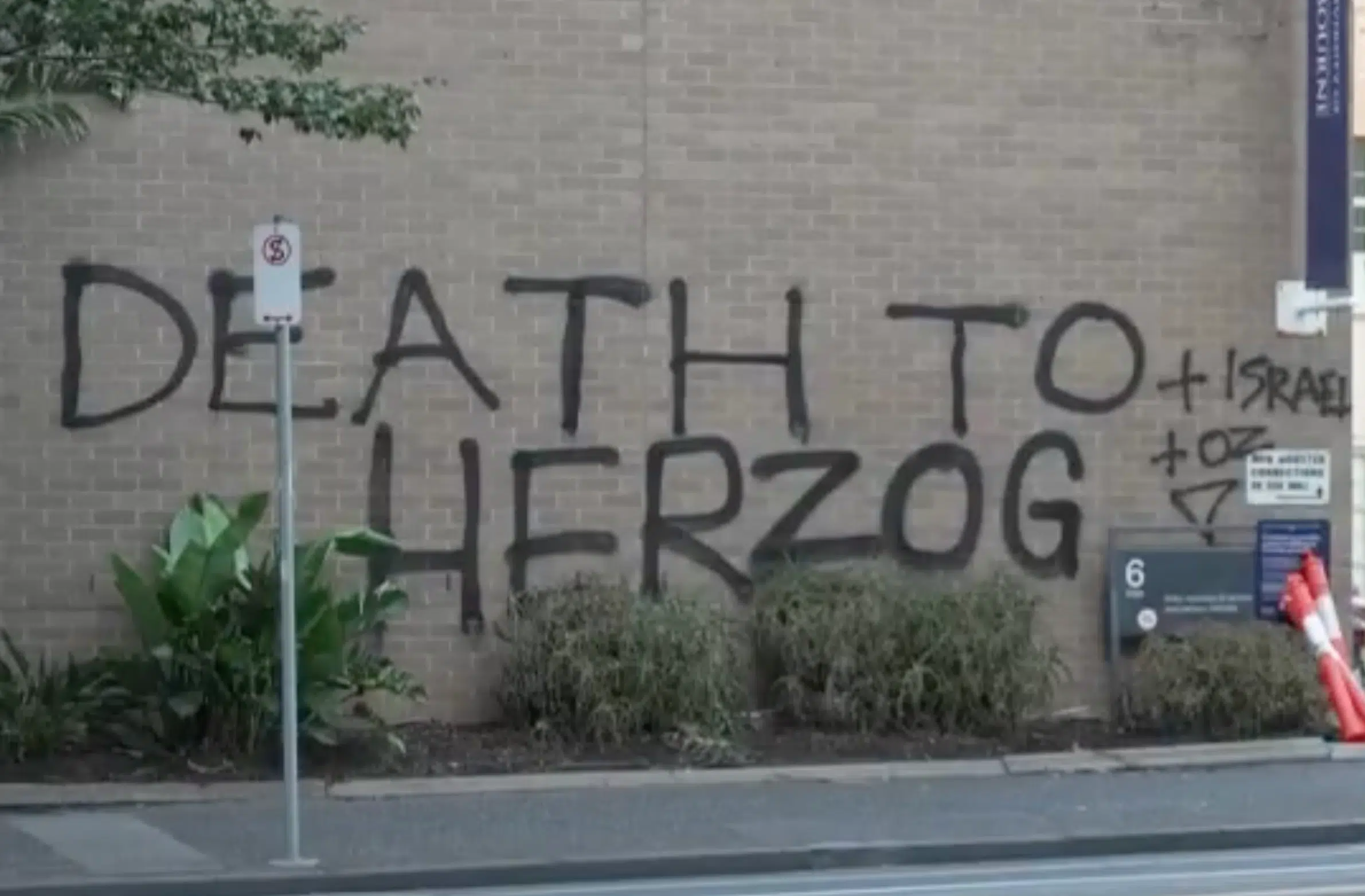

Mehdizade said the IHRA definition was essential because it exposed how modern antisemitism often hides behind extreme rhetoric about Israel. “This is not just about religion,” he said. “It is about humanity.”

Mehdizade pointed out that hatred of Jews today often came cloaked in political language. “People claim they are only anti-Israel,” he said. “But the Holocaust began with hatred of a people. It ended with genocide. That is the extreme version of this sickness.”

For Mehdizade, the IHRA definition is a necessary tool to identify and confront that threat. “We say never again, but we have to mean it,” he declared. “Whether you kill one Jew or thousands, it is the same hatred. The same ideology.”

Mehdizade spoke with emotion about the Holocaust, describing it as the ultimate warning of where unchecked hatred leads. “When someone talks about the Holocaust, I cannot stop crying,” he revealed. “I cannot understand how one group could kill another just for their beliefs. It is something crazy.”

Although he has not yet visited Auschwitz, Mehdizade has toured Holocaust museums in Europe. He plans to lead a visit there in 2026 with fellow imams and young Muslims. “We want to see it with our own eyes,” he said. “If we do not stand against this, it can return.”

For Mehdizade, adopting the IHRA definition is a starting point. The real test lies in what comes next. “Our duty as imams is to educate our communities,” he vowed. “Because if we stay silent, it will grow.”

Many young people encounter antisemitic narratives online or conflate the Israel-Palestinian conflict with hostility toward Jews. What are the most effective ways to educate youth to reject antisemitism and promote respectful discourse?

Ignorance fuels much of the antisemitism Mehdizade sees among youth in Europe and the United States. “They know nothing about Gaza,” he said. “Nothing about Israel. They don’t even know there are mosques and imams there. That Muslims have rights. When I tell them, they’re shocked.”

The most powerful remedy, Mehdizade believes, is direct exposure. “We must teach what really happens,” he said. “And we must promote visiting Israel, especially for young Muslims and imams, so they can see it for themselves.”

Mehdizade described a video showing an Arab Muslim woman in Israel, wearing hijab and working as a driver. “When asked if Jews mistreated her, she said never. Always, they respect me,” he recounted. “That’s the kind of story people need to hear.”

Even those who know the truth, Mehdizade noted, often refuse to accept it. “But ignorance is no excuse,” he said. “If I don’t know anything about a people, how can I hate them? The answer should be silence, not hatred.”

Mehdizade emphasized Islam’s closeness to Judaism. “When I post about Jews on Twitter, people ask if I’m a rabbi,” he laughed. “I say no, I’m an imam. But I believe Islam is the closest religion to Judaism.”

To underscore that connection, he added, “If all mosques were closed, and I had to choose another religion, Judaism or Christianity, I would choose Judaism. That’s how much we have in common.”

Mehdizade even pointed to dietary laws. “At Jewish conferences, I don’t ask what’s in the food,” he said. “I just eat. Kosher is like halal. I trust it. With others, I always ask.”

Education, honest engagement, and personal contact, he said, were the keys to moving young people from ignorance to understanding.

Have you faced backlash from within the Muslim community for your views? What’s been the most intense reaction you’ve encountered, and what gives you the resolve to keep going?

When Mehdizade speaks publicly about Jewish-Muslim relations, some initially object but often fall silent when he explains what Islam actually teaches. “They start to argue, but when I explain what is written in our religion, they have no response,” he said.

Mehdizade believes the deeper problem is a lack of sincere religious practice. “I’m not saying who’s a good or bad Muslim,” he stated. “But if someone doesn’t pray, doesn’t study, doesn’t practice anything, and then speaks about Jews or Israel, how can they speak with authority? Take care of your own home first.”

Many, Mehdizade said, were quick to jump into politics without spiritual grounding. “People focus only on the outside,” he observed. “They talk, they shout. But inside, it’s empty.”

Threats have become routine. “Yes, of course. Always. It’s part of my role,” he acknowledged. Still, he remains resolute. “As a Muslim and an imam, this is my first duty,” Mehdizade said. “If we don’t have coexistence, how can we live together in places like France or Israel, or anywhere? The world is multicultural. This is the reality.”

Critics have tried to discredit Mehdizade in every way possible. “They say I’m not a real imam. Or I work for Mossad. They try everything,” he recalled.

But Mehdizade is unfazed. “I believe in what I say. I believe in coexistence. And I will continue.”

If you could speak directly to both the Muslim and Jewish communities across Europe, what practical steps would you urge to build a future grounded in safety and mutual respect?

Interfaith events are meaningful, but they must lead to action, Mehdizade said. “Sometimes we attend a conference, we speak, we eat, we take pictures, and then it ends,” he commented. “That’s not enough.” These gatherings, he insisted, must be a beginning. “When I meet a rabbi or priest or imam, we already understand and respect each other,” he said. “But our communities don’t. They’re the ones who need this message.”

He sees it as a leader’s responsibility to return home and share what was learned. “I may speak for five minutes at a conference, but then I explain for an hour or more in my community — who I met, what I said, what I saw, and how it aligns with Islam,” Mehdizade said. “I don’t hide it.”

This, he believes, is the true mission of religious leadership. “Studying Islam for 12 years wasn’t the end,” he said. “It was the beginning. Now I must teach, correct misunderstandings, and guide people.”

Mehdizade warned of ideological poverty. “Some people have wealth, homes, success, but no understanding,” he posited/ “And toxic ideology can destroy lives and societies. It’s dangerous.”

In Islam, knowledge alone isn’t enough. “The best person isn’t the one who knows the most. It’s the one who acts,” Mehdizade said.

That consistent, visible, and honest action is what he sees as essential to building lasting peace. Mehdizade concluded, “We must act. We must teach. That’s how change happens.”