|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

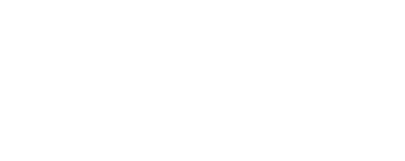

Darius Jones is the founder and CEO of the National Black Empowerment Council (NBEC), a coalition of Black American leaders focused on strengthening civic leadership, closing systemic gaps, and building strategic partnerships at home and abroad.

Widely respected for his work across business, politics, faith, and public life, Jones has emerged as one of the most consequential voices working to rejuvenate Black-Jewish relations. He grounds that work in firsthand experience, sustained engagement with Israel, and a moral framework shaped by the Civil Rights Movement.

In this interview withe the Combat Antisemitism Movement (CAM), Jones explains the NBEC’s mission, reflects on the impact of bringing Nelson Mandela’s granddaughters to Israel, examines the erosion and renewal of Black-Jewish ties, and outlines the leadership required to confront antisemitism and racism today.

For readers encountering the NBEC for the first time, how do you define its mission?

“The National Black Empowerment Council is a national organization that is increasingly becoming an international organization of grassroots Black leaders,” Jones said. “Our members come from business, politics, academia, technology, faith, philanthropy, and law enforcement.”

What defines NBEC, he explained, is not simply who its members are, but how they operate. “These are leaders who are deeply engaged in the civic life of the cities and communities they come from,” he said. “Having members across those critical industries, especially in cities with significant Black populations, allows them to work together to leverage their resources, their relationships, and their institutional influence for the uplift of the Black community.”

A defining feature of NBEC’s leadership model is firsthand exposure to Israel. “What makes our organization so unique is that every single one of our members has traveled to Israel,” Jones said.

That requirement reflects his own professional background. “I worked at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee for ten years,” he said. “During that time, I took hundreds and hundreds of Black leaders to Israel. I continued that model through NBEC because we found Israel to be a phenomenal example of collective self-determination, peoplehood, innovation, and resilience.”

Those experiences shape how leaders operate once they return home. “There is so much to learn from the birth of Israel, its preservation, and its continued advancement as a force for good in the world,” Jones said. “It informs and inspires how we show up as leaders in our own communities.”

That framework has also expanded NBEC’s reach beyond the United States. “That’s why we’re able to bring in leaders from other parts of the world, including people of the caliber of the Mandela family,” he said. “Not only into a movement of Black excellence, but into a movement of Black excellence committed to rebuilding a strong Black-Jewish and Black-Israel relationship.”

Your stance on Israel and the Black-Jewish relationship reflects clarity at a time of deep polarization. Where does that come from?

“My parents were involved in the Civil Rights Movement,” Jones recalled. “They always talked to me about how incredibly involved the brothers and sisters in the Jewish community were in making the civil rights movement the success that it was.”

That history became a guiding principle. “If somebody is there with you in your moment of trial and helps you achieve freedom and self-determination, you don’t get to a position of power and then turn your back on them,” he said. “You lean in. You stand with those who stood with you. That’s always been my worldview.”

Your recent delegation to Israel included Nelson Mandela’s granddaughters, Swati and Zaziwe. What motivated that decision?

“I’ve known Zaziwe, and in particular her husband David, for about twenty years,” Jones said.

When another Mandela family member became involved in anti-Israel flotillas, he explained, confusion spread about where the broader family stood. “Swati and Zaziwe wanted the opportunity to come to Israel themselves,” Jones said. “Their grandparents spoke highly of Israel, and they believed their cousin’s approach was irresponsible and intentionally designed to denigrate Israel.”

“They wanted to take a pro-Israel approach and have the journey culminate in Gaza, with them delivering aid to Palestinian women and children,” he added.

The visit included meetings across Israeli society. “They met with Israeli leaders, including President [Isaac] Herzog. They traveled to East Jerusalem. They met with Israeli Arabs and Palestinians,” Jones said.

The experience reshaped their understanding. “They left Israel with a truly deep and sincere conviction that Israel is doing what’s right,” he said. “They also came away deeply troubled by how the international media misleads people about Israel’s intentions, motivations, and even the consciousness of its people.”

“They wanted to help correct how people are really viewing Israel,” he added.

The sisters publicly rejected comparisons between Israel and Apartheid South Africa. Why was that moment so significant?

“I honestly can’t think of anything more impactful,” Jones said.

The late Nelson and Winnie Mandela, he explained, are synonymous not only with the fight against Apartheid, but with its defeat — and their granddaughters were old enough to remember it.

“They were of age. They were conscious of what was happening. They knew what Apartheid actually looked like. They lived it,” he said.

What they observed in Israel stood in direct contrast. “To be in Jerusalem and see people with my complexion,” Jones said, “to see Arab women in hijab, Orthodox Jews with the tendril curls, people with blonde hair and blue eyes, Asian people — so many different people from so many different backgrounds. All of them working together. Buying from each other. Sitting next to each other on buses and trains.”

He was unequivocal. “The visual of modern-day Israel is wholly incompatible with what Apartheid was,” Jones said. “They were looking at it and saying, ‘This looks nothing like what we experienced as children in South Africa.’”

The delegation also met with survivors of October 7th and families of hostages. How did those encounters shape the experience?

“Swati and Zaziwe are mothers,” Jones said. “Walking through Kfar Aza and hearing from women whose husbands were killed and whose children were taken hostage pulled powerfully on their humanity.”

One meeting stayed with them. The delegation spent extended time with Rachel Goldberg-Polin, whose son Hersh was taken hostage during the Hamas attack and later murdered in captivity.

“There is nothing like sitting across from a mother who has been shattered by that kind of loss,” he said. “Once you have those conversations, there is no room left for detachment.”

NBEC has been unapologetic about strengthening Black-Jewish and Black-Israel ties. How do you navigate backlash?

“I’ve done this long enough that people know who I am,” Jones said. “I’m publicly associated with both the Black community and Israel.”

“When people see Black leaders with unimpeachable credibility travel to Israel, come back, and continue fighting for their communities,” he said, “the narrative starts to shift.”

“It makes people stop and say, ‘Maybe I’m looking at the Israel piece wrong.’ That was always the strategy,” he added.

“They might not come back waving a flag, but it resets how they think.”

After the Civil Rights Era, what factors contributed to the erosion of the Black-Jewish alliance?

“Once the Civil Rights Movement succeeded, the role the Jewish community played in it was diminished,” Jones said. “Sometimes unintentionally, sometimes intentionally. There was a kind of erasure.”

Division, he said, did not happen in a vacuum. “There were provocateurs on both sides who fanned the flames,” Jones said.

What followed was a failure of leadership. “There weren’t enough leaders who took responsibility for restoring the relationship,” he said. “It was allowed to drift.”

Jones stressed that the cost of that drift was significant. “When Blacks and Jews stand together, we are a powerful force for good,” he said. “When we don’t stand together, we abdicate a responsibility and we lose that power.”

How do leadership exchanges with Israel advance NBEC’s long-term goals?

“When leaders travel to Israel, they no longer speak in abstractions,” Jones said. “They’ve gone in and out of bomb shelters. They’ve lived daily life.”

That firsthand experience, he explained, fundamentally changes how conversations begin once leaders return home. “They can sit across from Jewish counterparts and say, ‘This is not rhetoric. I was there,’” Jones said. “That creates a level of trust you cannot manufacture any other way.”

Exposure to Israel also opens the door to practical collaboration. “We meet leaders in cybersecurity, agriculture, and technology,” Jones said. “Israel wants to share knowledge with allies who actually understand its reality.”

Those relationships, he emphasized, move quickly from dialogue to structure. “NBEC has signed memoranda of understanding with Ben-Gurion University and Hebrew University,” Jones said. “We’re facilitating direct partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the United States.”

One such partnership was formalized with Texas Southern University in Houston, one of the largest HBCUs in the country. “African American students now have opportunities to study at Israel’s top universities,” Jones said. “At the same time, Ethiopian Israeli students, who are often disconnected from the broader Black diaspora, can come to HBCUs in the United States.”

For Jones, that reciprocity is the point. “This work isn’t symbolic,” he said. “It’s tangible. When you think creatively and actually execute, the mutual benefit becomes obvious.”

These exchanges “strengthen leadership politically, economically, and communally,” Jones said.

As antisemitism and racial extremism intensify, what kind of leadership is required now to rebuild the Black-Jewish relationship and prevent further fracture?

“It’s going to be incumbent upon leaders from both of our communities to be the adults in the room,” Jones said.

“All this chaos, all this division, all this antisemitism, all this racism is putting us on the precipice of disaster,” he said. “At a certain point, the inmates can no longer run the asylum.”

Action, he stressed, cannot wait. “No one is going to invite us to the table,” Jones said. “We’re not waiting for permission. We’re stepping up and doing the work.”

To learn more about NBEC and watch the Mandela delegation video, please visit: thenbec.org/videos/the-mandela-delegation