Interview: How the Jewish-American Hall of Fame Fights Anti-Semitism

Mel Wacks is a Jewish scholar from California with a remarkable story. Since 1969 he has issued over 50 different art medals depicting Jewish-American heroes and celebrities. Over the years Mel has documented the breadth of Jewish-American contributions to all areas of American society. More than 25,000 of these medals can be found in homes and museums stretching from London to Israel to China. Tamara Berens at CAM spoke to Mel Wacks to learn more about the Jewish-American Hall of Fame.

Mel was born to a secular family in the Bronx, New York. “We had a Christmas tree and did Easter when I was young,” Mel explains. He always had a passion for coins—stylistic collectible items that used to be featured in the pages of every major American newspaper. “I was a coin collector from the time I was 10 years old. Years later, I got interested in ancient Jewish coins and bought an ancient Jewish shekel.”

By profession, Mel was an engineer. “I went out to California where I worked on a top-secret reconnaissance aircraft. My wife never knew exactly what I was working on.”

One day he and his wife Esther were at the Sacramento State Fair in California and came across a huge menorah. It was from an exhibit in Berkeley, California, about 90 miles away. They traveled to Berkeley soon after and found themselves at the Judah L. Magnes Museum. Magnes, the first chancellor of Hebrew University and later its President, was a prominent rabbi who was born in nearby San Francisco.

As Mel describes, a man walking the halls of the Magnes Museum talked to him for a long period of time. Mel subsequently found out that he had been speaking to the museum’s very director. “I became consultant to the museum and the first project we did was wooden shekels. At that time medals were very popular in the United States.” As Numismatic Consultant, Wacks decided that the Magnes Museum should issue art medals, “portraying events and personalities in Jewish American history.”

“That’s how the Jewish-American Hall of Fame medal series was born.”

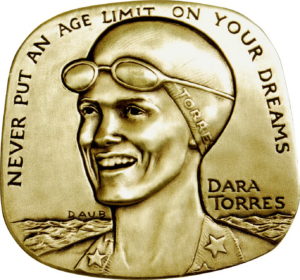

Today, Mel is the proud chairman of the Jewish-American Hall of Fame—a collection of art medals depicting the greatest living and dead Jewish-Americans. Launched with a donation of just $500 dollars, the project is now the longest-running series of art medals in the world.

“The purpose of it was to give an appreciation for Jews who made contributions to society, the arts, science, and so forth—and for non-Jews to appreciate what Jews had done, because anti-Semitism was always in the back of my mind. Lots of non-Jews have purchased the medals and have developed an interest in them.”

Mel celebrates the successes of Jewish-American heroes to inspire appreciation of the Jewish people from Jews and non-Jewish alike. Speaking on the phone from Los Angeles, California, where he lives, Mel talked me through some of his most interesting run-ins with Jewish history.

“Bess Myerson was the first—and only—Jewish Miss America winner in 1945, a politician in New York, and an entertainer. When we decided to [create a medal of] Bess Myerson, she invited me into her home and offered me some photographs that we could use.”

Myerson faced her fair share of anti-Semitism. “They asked her to change her name. And when she won Miss America, the winner is supposed to have contracts with pageant sponsors.” None of the pageant sponsors chose her as their spokesperson. In addition, Miss America winners typically make personal appearances. Myerson was invited to a country club, only to be told right before the event that there had been a mistake, and their club would by no means welcome a Jewish person.

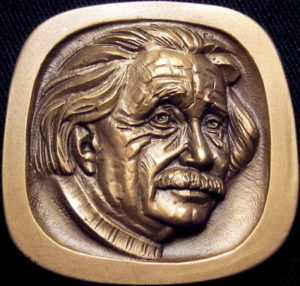

Beauty queens or not, each of Mel’s medals make their subject look like royalty. “Medals are high-relief. A coin is made by a press and it is hit one time, but an art medal is hit several times, so it brings up all the relief. A coin is shiny, but an art medal goes through several processes so that it has an antique surface sort of like a bronze statue.” The process for making the medals is time-consuming. Mel hires expert sculptors to create a portrait in a large basin of 8 inches in the same shape as the final model. From there, the clay model is converted to a hard model, which is mounted onto a special machine to produce a steel die. The die is then stamped onto metal “blanks” using great pressure.

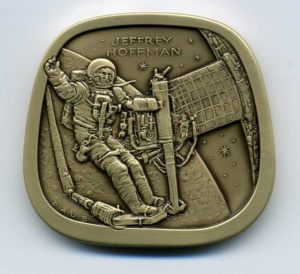

“I met Jeffrey Hoffman who was an astronaut; a Jewish astronaut.” Mel explains that many of the people in the Hall of Fame are Jewish “in name only.” “But Jeffrey Hoffman is not. When he went into space, he spun a dreidel in the air. It was Chanukah.”

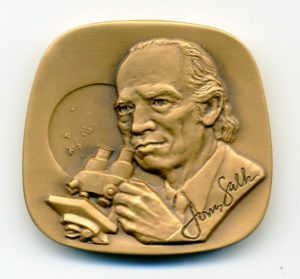

“But the most impressive meeting I had was with Jonas Salk.” Jonas Salk was a medical virologist who created the first successful polio vaccines.

“Hal Reed was the sculptor. We sent it to Salk, and he wasn’t happy with it—it didn’t quite capture him.” Mel was told by Salk’s staff that he would be in the Los Angeles area next week at a restaurant and was invited to meet him. “He was friendly and nice. The sculptor decided to ask him what was wrong with his portrait. Salk replied: “Look at me!” In the end, they managed to get it right.

For centuries, Jews were depicted as derogatory stereotypes on medals made throughout Europe. In the medieval period, the expulsion of the Jews from various European states was even celebrated through the issuing of popular medals. Mel’s project is an opportunity to do the opposite. He creates medals that instead celebrate the Jewish people.

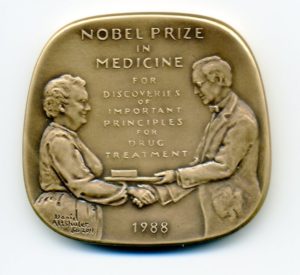

From 2011 onwards Mel made the decision to alternate between male and female medal honorees each year. Therefore, a number of women are featured in the Jewish-American Hall of Fame, including two who made notable scientific discoveries. “Gertrude Elion won the Nobel Prize in medicine. Her discoveries have saved more lives than Salk. She had a rough time as a woman in that industry.” Elion was a chemist who created the first chemotherapy for childhood leukemia, among many other accomplishments.

“Hedy Lamarr came over from Europe to escape the Holocaust. When she was here, she got a patent for frequency skipping which was supposed to prevent the Nazis from interfering with torpedoes launched from submarines to sink their ships. They never used her invention at the time because they didn’t take her seriously as a movie actress. But later on, her idea came to be used widely, including in mobile phones!”

For Mel, it is also important to showcase earlier Jewish contributions to American society. “One of the people who really made an important contribution is Haym Salomon who came over from Poland as a young man during the American Revolutionary War. He helped in many ways, including raising funds. He died relatively young and penniless and his widow tried to collect the money back that he had loaned to the fledgling nation. They never got anything back. Besides the money, his family asked for a medal to be made in his honor. There was a congressional committee that approved the medal, but it was never made. I like to think that the medal we made was instead of the one promised by the United States.”

When the Judah L. Magnes Museum was absorbed by the University of California at Berkeley in 2000, they discontinued their support of the Jewish-American Hall of Fame. So Mel had to find another home for the medals and the collection of 40 plaques commemorating Jewish-American contributions to the United States.

The Virginia Holocaust Museum offered to take the plaques. Though Mel did not originally intend for the Jewish-American Hall of Fame to be associated with the Holocaust, he felt it could in fact be quite fitting. “The idea is that this would show the achievements of the Jews. By killing 6 million Jews, the Nazis deprived the world of all the accomplishments these Jews and their descendants would have made in a variety of fields and endeavors.” Last year, the Skirball Museum in Cincinnati put up an exhibit featuring the Jewish-American Hall of Fame medals, and subsequently Mel gifted the collection to them.

Mel recognizes that medals are no longer the popular collectible they once were. “In the early days when we did this, I would send out a press release to the New York Times, back when they had a page with hobbies; stamps, coins, bridge, and chess. I became friendly with the coin columnist. When I sent a press release they would always print it, and I would literally get hundreds of orders.” Today, though there are no coin columns in any major newspapers, he is grateful for the patronage of loyal customers who return year after year to buy these medals―which has raised a quarter of a million dollars for Jewish non-profit educational organizations.

“As I get to know people who buy the medals, many of them say they love the Jews and Israel. Some are Christians and they are wonderful. One of my big collectors is in China. People have bought these medals for 30 or 40 years, and I have become friendly with them. I tell them they can always come to my home for a nice kosher meal.”

Mel’s February 2020 book, “Medals of the Jewish-American Hall of Fame” is available on Amazon. The Jewish-American Hall of Fame’s award-winning website is www.amuseum.org.