This article was authored by Ellie Rockoff, a Syracuse University student and Combat Antisemitism Movement (CAM) intern.

With antisemitism levels worldwide hitting levels unprecedented in the post-World War II era, it is more vital than ever for those who survived the Nazi horrors 80 years ago to have their voices heard. Yet the number of survivors is dwindling by the day, with only an estimated 250,000 remaining, and it is their stories that must be told and enshrined before it is too late.

One survivor who I have had the privilege of befriending is 92-year-old Elise Smith, formerly Elise VanDam, who lives today in Upstate New York. I was first introduced to Elise through the Syracuse Jewish and Family Service (SJFS) for an assignment I was writing on a Holocaust survivor grant initiative the New York State Office of Aging launched in 2022.

At our initial meeting, I was joined by Alise Gemmel, her SJFS social worker. I was apprehensive, not knowing what to expect. I didn’t even have any living grandparents myself, so how would I, a 20-year-old Syracuse University student, converse with a survivor of that same generation?

The reality of the moment hit me once I saw her extensive collection of Jewish literature, antique menorahs, and framed photographs of her pre-Holocaust life, all tangible time capsules offering a revealing glimpse into the past.

Elise was seven when Hitler’s troops arrived in her hometown of Antwerp, Belgium, in May 1940. Days later, Elise’s family, including her father, mother, and infant brother, were able to flee to France, where there were boats taking Jewish refugees to England. Elise remembers sleeping in a forest, huddled tightly with her family, looking for the signal to board.

“The Nazis were exactly five hours behind us,” she told me. “Had the tide not changed or come as it was supposed to, I would not be here today. We would’ve been killed by the army that was behind us.”

The VanDams reached London during the Blitz, dodging Luftwaffe bombs as they waited for their American immigration papers to be approved — an especially onerous process for Jewish refugees at the time.

“We slept every night on the cement floors…for months at a time, as London was being bombed. Every single night,” Elise recalled.

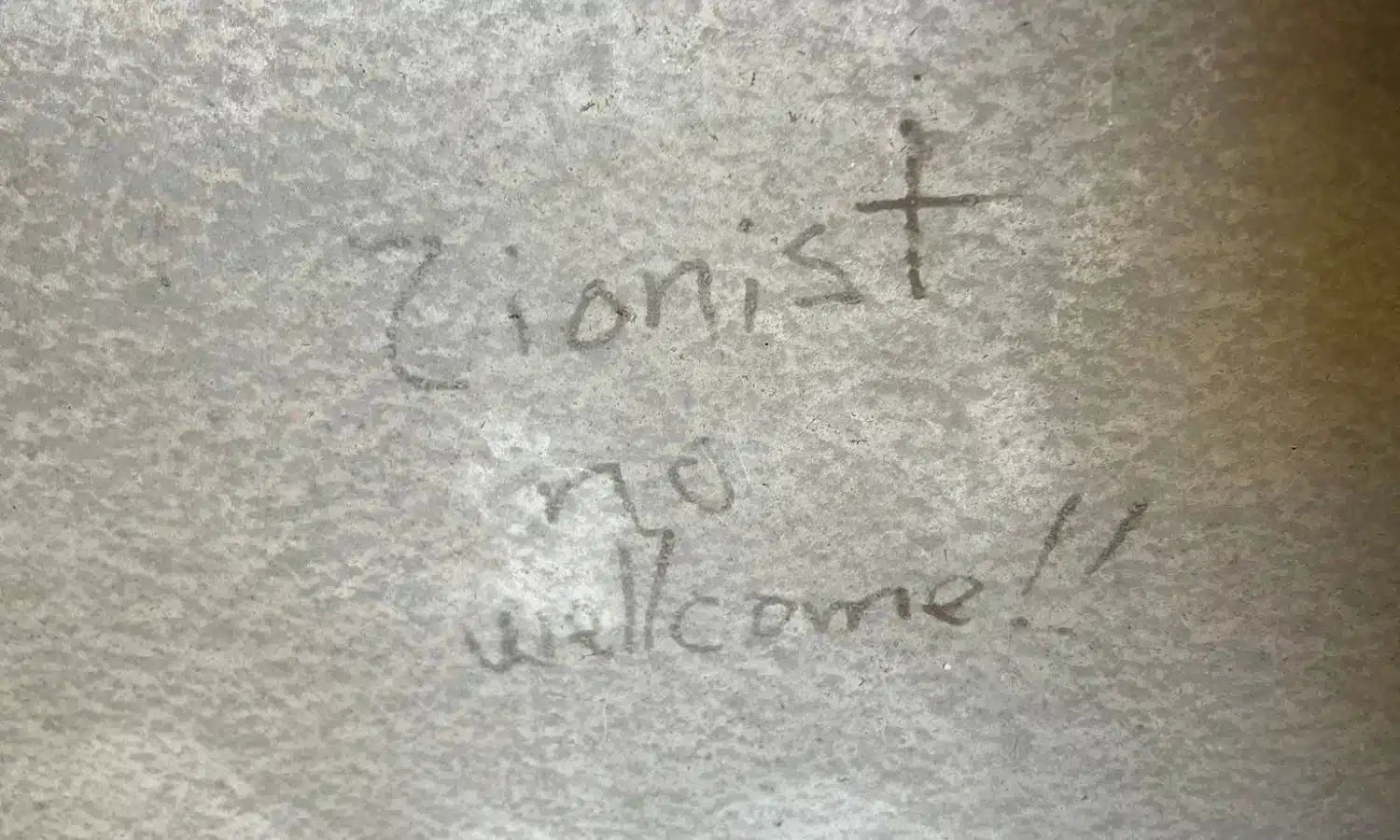

After a dangerous four-week trans-Atlantic journey under the threat of German U-boats, the VanDams arrived in New York City. They settled in Queens, where the antisemitism they escaped from in Europe followed them in new forms.

“I learned a word called ‘segregated,’” Elise said. “Where Jewish people couldn’t live in certain communities, couldn’t go to country clubs or summer camps for children for several years…this was a rough time.”

Even after World War II ended, Elise’s childhood was haunted by memories of what they had been left behind in Belgium. “I lost the parents of my father and his sister,” she said. “They went to Bergen-Belsen, and they were killed in the camps. There were several other members of our family, older men and women who were also taken to the camps. So we had family that went into the horrors of the camps, that they never heard from again.”

Elise went on to earn a nursing degree, worked for periods in both the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia, and was married twice, having two sons.

She was long reluctant to share her story, saying she often felt a “cold wall” from people because of her Jewish faith. But now, in her old age, her attitude has shifted.

“I’ve told you things that I haven’t really opened up so much because I don’t want to remember,” Elise said. “I’m honored — I’m talking to you and you’re accepting it all. It’s a gift, sweetie.”

She added, “If it only can reach somebody and open their mind. Why several thousands of years later does this [antisemitism] continue?”

This question cuts deep, amid the eerie parallels between Elise’s childhood experiences and the surge of antisemitism sweeping across the globe today, including in the United States. She cries, “This is America. Land of the free and home of the brave. What happened to that magic land that everyone came to? We came to it to escape. We were so thankful to be here.”

As someone isolated from the internet and social media, it is hard for Elise to comprehend the full extent of the contemporary proliferation of antisemitic behavior and rhetoric, particularly in the aftermath of the October 7th massacre in Israel.

It is heartbreaking to sit beside her worn recliner, holding her frail hand, and listen to the stories of what she suffered. Soon, there will be no survivors to tell their firsthand accounts of the Holocaust, meaning the younger generations, including my own, must listen now and pass along the enduring lessons to those who will follow us.

Yes, this responsibility is fraught with pressure, but also pride. My generation will be the final one with contact with living survivors, whose words may be the most convincing and effective tool in countering the antisemitic misinformation fueling the false narratives we see today.

We cannot let the memory of the Holocaust fade into history. There is simply too much to lose.