School-Yard Anti-Semitism: The Antidote is Holocaust Education

By Dalya Meyer (Tulane University, Class of 2022)

Last year my home state of Oregon, became the 12th state to adopt legislation requiring schools to provide Holocaust education. The law stipulates that instruction must be designed to “prepare students to confront the immorality of the Holocaust, genocide, and other acts of mass violence and to reflect on the causes of related historical events.” While it is important for students across the world to learn about the Holocaust, the legislation does much more than provide new teaching guidelines. In a state whose Jewish community accounts for less than 1% of the population, the legislation pushes schools to embrace cultural diversity, and to teach students the importance of human rights alongside the consequences of blind ignorance and hate.

When schools fail to educate their students to welcome diversity and to understand an assortment of histories, it should come as no surprise that young people will think it is acceptable to mock people of different backgrounds. The lack of universal Holocaust and tolerance education across the United States and in other countries, has had harmful consequences. In Italy, the percentage of Italians that believe the Holocaust never happened increased from 2.7% in 2004 to 15.6% in 2020. Further, nearly three-in-ten Americans say they are not sure how many Jews died during the Holocaust and in France, 20% of young adults have never heard of the Holocaust.

Anti-Semitism is not just physical and emotional violence towards the Jewish people, it is a deep-seated negative perception of Jews that has infected different elements of society for centuries. The students spewing hatred and promoting anti-Semitic stereotypes may not even be aware of the bias shaping their actions. When young people lack effective education teaching them to deconstruct these harmful biases, their ignorance only grows.

When I was in third grade, a peer of mine doodled a swastika onto his paper during class. I was eight years old and did not yet know what the Holocaust was, so the drawing meant nothing more to me than an innocent scribble. The boy informed my table, however, that he was coloring “Hitler’s Flag.” While the conversation may have felt innocent at first, that innocence was lost when the boy looked me in the eye and said: “Hitler would have hated you. You would have been killed first.” I was taken aback. “Why?”. His response was only four words: “Because you’re a Jew.”

From then on, I knew I was different. Many Jewish-Americans have experienced similar stories of “casual anti-Semitism” while growing up, and with those stinging words, I understood that my Jewishness was not always welcomed by others.

As I grew older, and my understanding of my Jewish identity expanded, I felt the ignorance of my non-Jewish classmates grow as well. I remember having to sing a Hanukkah song for my school’s Christmas assembly, and watch the kids around me snicker and make comments such as “the ‘Jew song’ is ruining the assembly”. In the 6th grade, I stood as an uncomfortable bystander as boys mocked Jews by wearing fake Kippot. That same year, when reading a book about the Holocaust in class, a boy singled me out as a Jew, and posed the question, “Aren’t all Jews rich? Why didn’t they use their money to fight back against the Nazis? I thought Jews were smart.” I didn’t know how to respond.

Holocaust jokes became the norm, and while they were not always directed at me, I could not help but nervously shift in my seat as I would hear students joke about Jews belonging in “ovens.” Witnessing this kind of anti-Semitism as a schoolchild also begs the question, from whom did these children learn this behavior? These grade school experiences proved to me that without effective education on the Holocaust, we are allowing anti-Semitism, and other forms of hate to grow among our youth, passing these attitudes on to the next generation. In today’s world, these issues are further exacerbated by students sharing hateful conduct to their peers on social media. The anti-Semitism that fills headlines covers the most provocative attacks however, the casual anti-Semitism of the schoolyard slips through unnoticed.

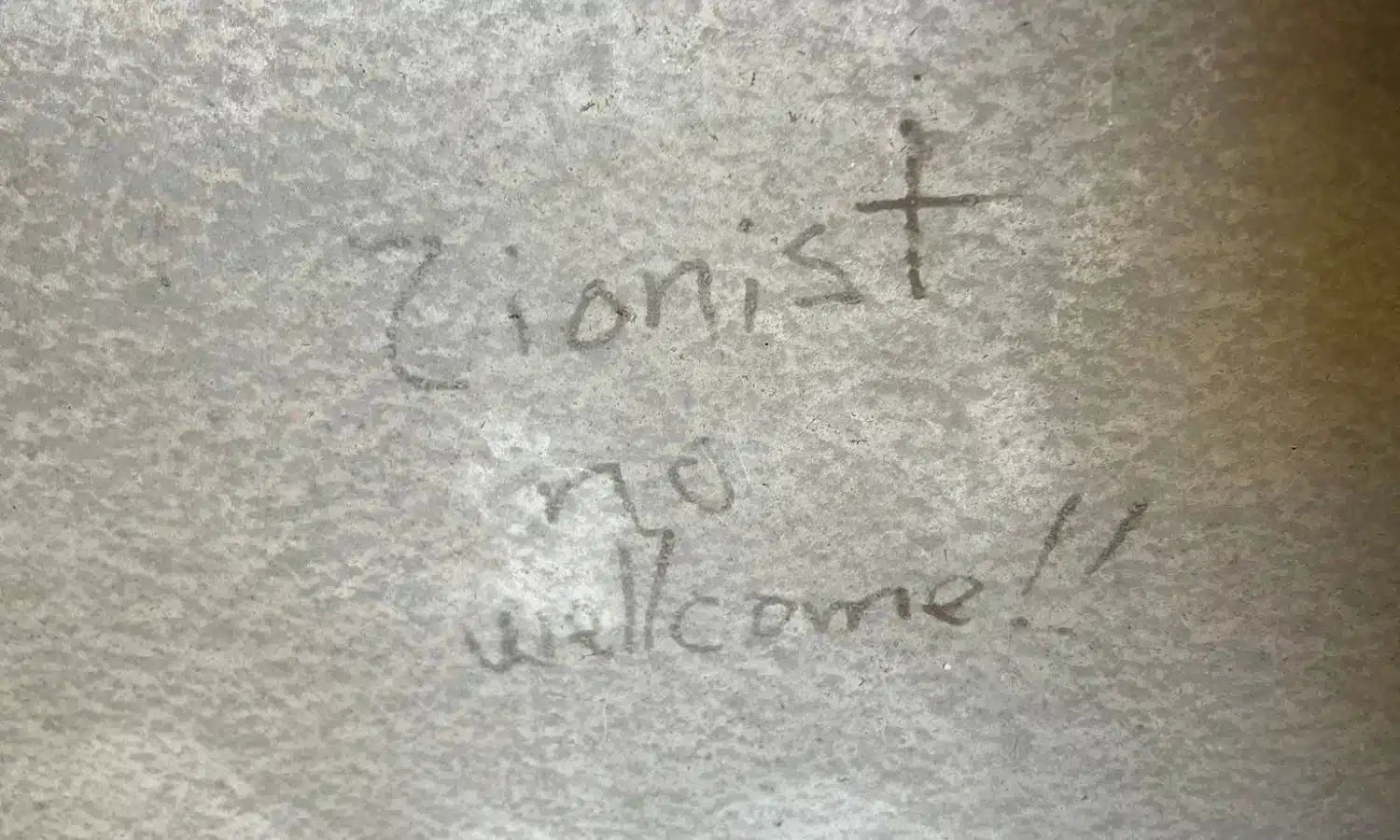

As a college student, I hoped that my classmates would by now have learned enough history and empathy to diminish their casual anti-Semitism, but that is not always the case. With time, schoolyard anti-Semitism morphs into real-world anti-Semitism. We are seeing this at marches to fight for social justice across the country, where Jews, as assumed Zionists are told they are not welcome. This is happening blocks away from my high school in Portland, where a protester once stood outside holding a Palestinian flag and a sign saying “the Jews are meeting in DC to plot how Zionists can control the world.”

In 2019, the Anti-Defamation League reported that anti-Semitic incidents in schools increased by 20%, and those are just the reported cases. While the rise in anti-Semitism both inside and outside of the classroom is devastating, it is not shocking. In a nation as diverse as the United States, a lack of Holocaust and tolerance education naturally leads to gaps in awareness and empathy among children, with long-term consequences. Holocaust education is something that should not just be taught in one lesson during a high school history course, but incorporated into curricula for students as young as elementary school. If states across America followed Oregon’s lead and all schools began to adopt mandatory Holocaust and tolerance education, alongside the history of Jewish Americans and other marginalized groups, we may begin to see a change in the next generation of children.