|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Table of Contents

Toggle

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat Is Antisemitism?

At its core, antisemitism refers to prejudice, hatred, or discrimination against Jews—whether directed at individuals, the Jewish people, or the Jewish state. Yet the antisemitism definition goes far beyond a dictionary entry. It describes a relentless, shape-shifting hatred that has endured for centuries by adapting to the ideologies, politics, and the social zeitgeist of each era.

From medieval blood libels to racial pseudoscience to today’s efforts to delegitimize the State of Israel, the accusations evolve with the times, yet the Jew remains the eternal scapegoat. Antisemitism scholar Robert Wistrich captured this obsession, calling it both “the longest hatred” and “a lethal obsession.”

This adaptability is not confined to history. Whether a swastika on a synagogue wall, a viral video about “Jewish control,” or campaigns to boycott Israel, all reveal the same antisemitism meaning: blaming Jews for society’s recurring fears and failures—accused of being both too rich and too poor, too powerful and too powerless, too insular and too controlling. These contradictions are deliberate, and they are what make antisemitism so persistent.

So, what is antisemitism really? It is both ancient and alarmingly modern. Cloaked first in theology, then in race science, and now in the language of human rights, it adapts to every age, yet its object of hatred has never changed: the Jewish people.

Only a clear antisemitism definition can expose these disguises across time. Without it, antisemitism slips into denial, masquerades as activism, and hides behind claims of justice. That is why understanding the full antisemitism meaning is essential—not as theory, but as a guide for action. A precise antisemitism definition is not academic—it is a moral and practical imperative to safeguard Jewish life today and for generations to come.

Why a Shared Antisemitism Definition Matters

A precise antisemitism definition provides the practical lens needed to recognize this hatred across contexts—from classrooms to courtrooms. Such clarity allows institutions to distinguish genuine criticism of Israeli policy from discriminatory hate. Without it, responses splinter, loopholes are exploited, and Jewish concerns are too easily dismissed.

By contrast, a strong and widely accepted antisemitism definition eliminates ambiguity. It empowers governments, schools, universities, and civil society to identify, document, and combat Jew-hatred consistently. It also anchors legal enforcement, education policy, workplace protections, and evidence-based threat responses.

This clarity matters across every sector. Law enforcement can classify hate crimes with precision. Journalists can report responsibly, avoiding harmful stereotypes. Educators can teach about antisemitism—past and present—without confusion. Employers and tech platforms can uphold standards against hate. International institutions, whether on university campuses, at the EU, or at the UN, will face limits on excusing or mislabeling antisemitism.

In short, a shared antisemitism definition not only ensures consistency across institutions—it transforms recognition into accountability. It also grounds the antisemitism meaning in real-world practice, answering the urgent question: what is antisemitism today?

The Evolution of Antisemitism Over Time

Antisemitism mutates with every age, yet its target never shifts. To grasp the antisemitism meaning today—and to truly answer what is antisemitism across history—we must confront a hatred that renews itself endlessly, ensuring that Jews remain marked as the world’s perennial target.

Religious Antisemitism: Blood Libels and Persecution

Religious antisemitism began with the charge of deicide — the accusation that Jews were collectively responsible for the death of Jesus. For centuries, this teaching branded Jews as eternal enemies of Christianity, unredeemable and uniquely guilty. From this foundation grew further myths: Jews as ritual murderers, desecrators of the Eucharist—the Christian sacrament of bread and wine viewed as the body and blood of Christ—and well-poisoners during the Black Death.

These charges fueled eruptions of violence. In 1096, mobs following the First Crusade massacred thousands of Jews in the Rhineland, one of the earliest large-scale assaults on European Jewry. Soon after, fabricated accusations spread across the continent. The first recorded blood libel, in Norwich in 1144, set the template for ritual murder charges that persisted for centuries. Accusations of host desecration—the charge that Jews abused or profaned the consecrated communion wafer, believed by Christians to embody the body of Christ—led to mob attacks and mass burnings, while plague years saw Jews massacred by the tens of thousands in cities such as Strasbourg and Basel after being scapegoated for spreading disease.

Over the following centuries, expulsions swept Western Europe—England (1290), France (1306), and Spain (1492)—casting Jews as permanent outsiders.

Expulsions, Forced Conversions, and Eastern Tragedies

Forced conversions became another recurring weapon. Pogroms in 1391 across Castile and Aragon produced mass baptisms and the emergence of conversos. The Alhambra Decree expelled Spain’s Jews in 1492, while Portugal’s 1497 edict compelled baptism for those who remained, often forbidding legal emigration. Earlier, under Visigothic rule in 613, Jews were ordered to convert; centuries later, church councils entrenched similar coercive measures.

In the Islamic world, Jews faced parallel trials. Under the Almohad caliphs of the 12th–13th centuries, Jews and Christians were forced to choose conversion, exile, or death—prompting figures like Maimonides to flee. Even in calmer times, Jews lived under dhimmi status—a protected but second-class position for non-Muslims under Islamic rule. They were tolerated but subordinate, burdened with the jizya, a special poll tax imposed on non-Muslims, and other legal disabilities.

Eastern Europe, initially a refuge, became the site of devastation in 1648–49, when Cossack uprisings under Bohdan Chmielnicki killed tens of thousands of Jews in Ukraine and Poland. Remembered as the Gzerot Tach ve-Tat, these massacres shattered centuries of Jewish life and left a lasting scar on collective memory.

These religious tropes never disappeared. Accusations of bloodlust, sacrilege, and deicide resurface even today in propaganda, sermons, and online hate. That is why any credible antisemitism definition must account for these recurring myths, which have fueled persecution across continents and centuries.

Racial Antisemitism: Pseudoscience and Genocide

By the 18th and 19th centuries, traditional religious prejudice was refashioned into racial pseudoscience. Influenced by emerging theories of social Darwinism and racial hierarchy, Jews were no longer condemned for their beliefs but branded as an alien “race,” biologically inferior and inherently dangerous.

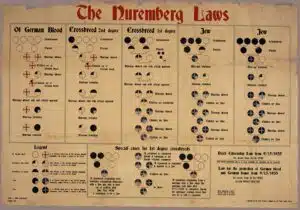

This marked a profound break with the past. Where coerced conversion had once offered a dubious and sometimes temporary escape from persecution, racial antisemitism closed the door completely. Jewishness was redefined as immutable ancestry. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 codified this worldview, decreeing that even baptized Jews and their descendants were Jewish by blood—stripped of rights, excluded from society, and marked for destruction.

These doctrines reached their deadliest expression under Nazi Germany. Across occupied Europe, Jews were forced into ghettos, deported in cattle cars, and annihilated in extermination camps. The Holocaust—the industrialized murder of six million Jews, including 1.5 million children—was racial antisemitism in its most unrestrained, genocidal form.

Yet 1945 was not an ending. Soviet propaganda retooled these racial myths into accusations of “Zionist conspiracies” and “cosmopolitan disloyalty,” culminating in purges and the infamous Doctors’ Plot of 1952, when mostly Jewish physicians were falsely accused of conspiring to kill Soviet leaders. In the Middle East and North Africa, Nazi imagery and tropes were recycled to portray Jews and Zionism as existential threats. What had once been justified through religion, and then through race, was now recast in political language—laying the foundation for much of contemporary antisemitism.

That trajectory underscores why any serious antisemitism definition must account not only for religious and racial myths of the past but also for how they continue to shape modern incarnations of Jew-hatred.

Contemporary Antisemitism: Targeting the Jewish State

As open antisemitism grew taboo in postwar Western discourse, its focus shifted from the individual Jew to the State of Israel—the proverbial “Jew among the nations.” Where religion had once branded Jews as Christ-killers and heretics, and race had marked them as biologically impure, politics now targeted their restored sovereignty. Zionism—the movement for Jewish self-determination—was reframed not as liberation but as oppression.

In 1975, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 3379 declaring “Zionism is [a form of] racism.” The vote—driven by the Soviet bloc, Arab states, and the Non-Aligned Movement—was a calculated campaign to delegitimize the Jewish state and recast Jewish nationhood as a crime against humanity. Just three decades after the Holocaust, as the Jewish people rose from the ashes of Auschwitz to reclaim sovereignty over their land, the UN branded that rebirth illegitimate. Although the resolution was revoked in 1991, its damage continues to linger in political discourse.

Weaponizing Human Rights Against the Jewish State

This distortion weaponized the language of human rights itself. By redefining Zionism as racism, the UN handed antisemites a new political vocabulary—disguising the world’s oldest hatred as modern human rights discourse. That is the antisemitism meaning in our time: cloaking hostility toward Jews as justice.

That legacy endures in chants and slogans that openly call for Israel’s destruction while masquerading as activism. “From the river to the sea” is a call for the elimination of the Jewish state, while “Globalize the Intifada” is a call for violence against Jews everywhere. False allegations of genocide and apartheid have become rallying cries at protests and in international forums, weaponizing the rhetoric of human rights to vilify Israel. These accusations, repeated in graffiti, resolutions, and campaigns, recycle the same ancient lies in modern disguise.

Today’s antisemitism exposes the lethal consistency of this hatred. Each era invents new rhetoric—Christ-killers, racial parasites, colonial oppressors—but the message never changes: Jews are uniquely illegitimate, whether as individuals or as a nation. The so-called “new antisemitism” is nothing new—it is the oldest hatred reborn in political form, now aimed at the Jewish state.

Durban 2001: A Watershed for Modern Antisemitism

The postwar taboo on open antisemitism did not last long. By the early 2000s, the political reframing of Jew-hatred—once declared at the UN with ‘Zionism is racism’—found its most brazen expression at the 2001 United Nations World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa, which produced the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action. Marketed as a milestone for equality, Durban instead became a watershed moment for embedding antisemitism in the very language of human rights. Legal scholar Anne Bayefsky, who documented the proceedings, described it as “a racist anti-racism conference.”

A Forum for Hate, Not Justice

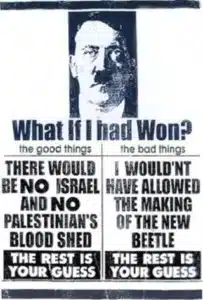

More than 3,000 NGOs attended the parallel NGO Forum, which quickly descended into an antisemitic spectacle. Without a clear antisemitism definition in place, hatred flourished unchecked. Copies ofThe Protocols of the Elders of Zion circulated freely. Flyers showed Adolf Hitler with the caption, “What if I had won? There would be no Israel.” Terrorist groups were praised as “resistance movements.” Jewish and Israeli delegates were shouted down, harassed, and in some cases physically threatened, forcing some to walk out for their own safety.

The forum’s final declaration revived the slander “Zionism is racism.” For Jewish participants, the betrayal was devastating. What had been billed as a global stand against hatred became, instead, one of the most hostile international assaults on Jews since the Holocaust.

Durban’s Lasting Damage

Durban set the blueprint for modern antisemitism: branding Israel guilty of genocide and apartheid, and recasting hostility to Jewish self-determination as “justice.” Out of this framework emerged the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign. Marketed as a human rights movement, BDS adopted Durban’s playbook—using economic, cultural, and political isolation to strangle Jewish sovereignty out of existence.

The damage did not end in 2001. Durban’s toxic legacy was carried into later UN “Durban Review Conferences.” In 2009 (Durban II, Geneva), Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad used the platform to call Israel a“racist government” established on the “pretext of Jewish suffering.” In 2011 (Durban III, New York), the UN again gave legitimacy to an agenda rooted in demonizing the Jewish state. Many democratic nations, including the United States, Canada, Germany, France, and the UK, boycotted these conferences, underscoring how Durban had come to symbolize the hijacking of human rights for antisemitic ends.

Durban did not merely fail to combat racism; it legitimized and globalized a new form of it. By granting antisemitism international respectability under the banner of human rights, it left Jews exposed in the very institutions meant to defend equality. That is why only a clear antisemitism definition can answer the question what is antisemitism in practice and ensure that the language of justice is never again turned into a weapon against the Jewish people.

Sharansky’s 3Ds: Distinguishing Criticism from Antisemitism

If Durban revealed how antisemitism could cloak itself in the language of human rights, it also underscored the urgent need for clarity. Filling that vacuum, Natan Sharansky—Soviet dissident, human rights icon, and now CAM Advisory Board Chair—articulated a framework that changed the global conversation: the “Three Ds.”

The Three Ds: Demonization, Double Standards, Delegitimization

Sharansky’s insight was simple but transformative: the need to draw clear red lines between criticism of Israel and antisemitism. To provide that clarity, he articulated three tests — Demonization, Double Standards, and Delegitimization — that unmask when rhetoric crosses from legitimate debate into hate.

First, Demonization. When Israel—or Jews more broadly—are portrayed as uniquely evil. Comparisons to Nazis, medieval blood libels recast in modern cartoons, or conspiracy theories painting Jews as malevolent forces are not critiques of policy but indictments of existence itself.

Second, Double Standards. When Israel is falsely singled out for crimes it has not committed, while the world turns a blind eye to genuine atrocities elsewhere. At the UN Human Rights Council, Israel has been condemned more than all other countries combined — not because it is guilty of genocide or ethnic cleansing, but because it is held to standards applied to no other nation. Boycotts and exclusion campaigns target Israel alone, even as regimes that do commit mass slaughter or ethnic cleansing constantly escape scrutiny. Such disproportionality is not fairness — it is bias cloaked in the language of justice.

Finally, Delegitimization. The outright denial of Israel’s right to exist. Declarations that “Zionism is racism,” calls for a “one-state solution” designed to erase Jewish sovereignty, or claims that Jews uniquely have no right to self-determination are not debates over borders — they are rejections of Jewish nationhood itself.

The Lasting Impact of the 3Ds

Together, these 3Ds restored the moral compass Durban had obscured. They made it possible to distinguish between legitimate criticism of Israeli policies and antisemitism in disguise. Lawmakers, educators, NGOs, and scholars soon adopted the 3Ds as a practical tool to evaluate rhetoric and policy. The framework quickly gained traction in parliaments, NGOs, and campus forums, providing a test for distinguishing criticism from antisemitism years before the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) codified the standard.

More importantly, the 3Ds laid the intellectual and moral groundwork for what would become the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism — now the global benchmark. In this way, the 3Ds were not only a response to Durban’s abuses but a reclaiming of moral language itself. Where Durban weaponized human rights against the Jewish people, Sharansky reframed those rights as their defense. He provided the clarity needed to answer what is antisemitism in practice — ensuring that the world’s oldest hatred could no longer hide behind the rhetoric of justice.

IHRA Antisemitism Definition in Action: 11 Examples

The IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism—endorsed by more than 1,200 entities—goes beyond theory. It translates the antisemitism definition into action by laying out 11 concrete examples of how Jew-hatred manifests today. For readers asking what is antisemitism and how it looks in practice, these examples illustrate its presence on streets, campuses, in the media, and online. They turn the antisemitism meaning from an abstract concept into a practical framework for recognition and accountability.

1. Calling for, Aiding, or Justifying Violence Against Jews

- Glorifying the October 7th massacre or other terror attacks against Jews by calling them “resistance.”

- Chanting slogans such as “Death to Israel,” “Globalize the Intifada,” or “From the River to the Sea.”

- Displaying symbols like the inverted red triangle to mark Jewish targets, or the ‘Red Hands’ emblem—recalling the 2000 Ramallah lynching of Israeli soldiers—as visual calls for violence.

Why it qualifies: Calls to violence strip Jews of their most basic right to safety and legitimize bloodshed.

2. Stereotypes and Conspiracy Allegations About Jewish Power

- For example, alleging that Jews secretly control governments, finance, or the media.

- Promoting myths such as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

- Claiming that “the Jews” orchestrated events like 9/11.

Why it qualifies: These accusations fuel paranoia and hate, inspiring pogroms in the past and extremist violence today.

3. Blaming Jews Collectively for Wrongdoing

- Branding Jews collectively as “Christ-killers.”

- Generalizing hostility toward moneylenders into the stereotype that all Jews are greedy.

- Portraying one Jew’s alleged crime, like the Dreyfus Affair, as proof of collective guilt.

Why it qualifies: It erases individuality and condemns an entire people for the alleged acts of one.

4. Holocaust Denial

- Claiming the Holocaust is a “myth” or fabrication.

- Alleging that gas chambers never existed.

- Portraying the Holocaust as “Zionist propaganda.”

Why it qualifies: Denial desecrates the memory of six million Jews and encourages future crimes by pretending none occurred.

5. Accusing Jews or Israel of Inventing or Exaggerating the Holocaust

- Accusing Jews of exaggerating the Holocaust to justify Israel’s existence.

- Alleging that Jews exploit Holocaust remembrance for political gain.

- Claiming that Holocaust education is “propaganda” rather than history.

Why it qualifies: This tactic twists Holocaust memory into a weapon against Jews.

6. Accusing Jews of Dual Loyalty

- Alleging Jews are more loyal to Israel than to their own country.

- Casting Jewish officials, students, or professionals as untrustworthy solely for supporting Zionism.

- Suggesting Jewish political participation is driven by foreign allegiance.

Why it qualifies: The dual-loyalty slur paints Jews as perpetual outsiders whose patriotism is always suspect.

7. Denying Jews the Right to Self-Determination

- Branding Israel’s existence as a “racist endeavor.”

- Rejecting Jewish peoplehood and sovereignty as illegitimate.

- Arguing Jews alone, among all peoples, have no right to a homeland.

Why it qualifies: Denying self-determination uniquely to Jews erases identity and sovereignty.

8. Applying Double Standards to Israel

- Subjecting Israel to more UN resolutions than all other nations combined.

- Demanding sweeping boycotts of Israel while ignoring governments guilty of genocide or ethnic cleansing.

- Calling for Israel’s exclusion from sports and cultural events while abusive regimes face no such bans.

Why it qualifies: These accusations are false. Legitimate criticism applies equal standards; singling out Israel with fabricated charges reveals discrimination, not fairness.

9. Using Classic Antisemitic Imagery to Characterize Israel

- Reviving blood libel motifs, portraying Israelis as child-killers.

- Recycling Nazi-style caricatures—grotesque, parasitic, animalistic—onto Israelis.

- Depicting leaders with hooked noses, bloodstained hands, or demonic features.

Why it qualifies: Dehumanizing imagery incites violence and repackages ancient hate for modern audiences.

10. Drawing Comparisons Between Israel and Nazis

- Equating Israel’s actions with Nazi persecution of Jews.

- Comparing Israeli leaders to Hitler.

- Portraying the Star of David as a swastika.

Why it qualifies: These claims invert history, trivialize genocide, and weaponize Jewish trauma against the Jewish state.

11. Holding Jews Collectively Responsible for Israel’s Actions

- Harassing Jewish students on campus over Israeli military actions.

- Vandalizing Jewish-owned shops with “Free Gaza” slogans.

- Defacing synagogues with “Free Palestine” graffiti.

Why it qualifies: This erases Jewish individuality and targets Jews everywhere as proxies for Israel.

The Stakes: Why a Shared Antisemitism Definition Is Essential

Without a clear and widely accepted benchmark, responses to antisemitism remain fragmented. Ambiguity allows perpetrators to exploit loopholes, while institutions minimize or mislabel hate. The IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism closes that gap, ensuring governments, universities, and civil society act with consistency and credibility. By clarifying the antisemitism meaning, IHRA prevents leaders from hiding behind vagueness or denial.

Ultimately, the IHRA antisemitism definition is more than a description—it is a defense against distortion and inaction. Anchoring education, law, and policy to the IHRA antisemitism definition equips societies to confront Jew-hatred with precision, urgency, and resolve. That is why IHRA has emerged as the most authoritative standard worldwide—not only defining antisemitism, but giving institutions the clarity and tools to fight it.

What Makes the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism So Effective

The IHRA antisemitism definition is not theoretical—it captures the lived antisemitism meaning Jews face daily. From chants for violence on city streets to boycotts on campuses and conspiracy theories online, IHRA names these threats clearly and transforms recognition into accountability.

Most importantly, IHRA shows that antisemitism is not confined to swastikas or slurs. It operates on a continuum of threats that, left unchecked, erode both the security and dignity of the Jewish people. Recognizing these realities equips societies with a practical framework to act before hate escalates further.

What sets IHRA apart is how it connects principle to practice. Unlike vague or outdated frameworks, it defines not only what antisemitism looks like in theory but how it manifests in classrooms, parliaments, protests, and online spaces.

1. It Reflects Today’s Reality

Antisemitism is not frozen in the past—it mutates. IHRA captures its modern forms, from Holocaust denial and conspiracy myths to anti-Zionist rhetoric on campuses and across social media. It defines antisemitism as a lived, evolving threat rather than a relic of history.

2. It Provides Practical Guidance

IHRA’s 11 examples turn principle into practice, offering a shared framework for action—from classifying hate crimes to shaping campus policies, legislation, and online moderation. In short, the antisemitism definition bridges the gap between recognition and response.

3. It Has Global Endorsement

As of February 1, 2025, the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism has been adopted by 1,266 entities worldwide. Among them are 46 countries—including the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Canada—reflecting broad international consensus. In the U.S., 37 states and 98 city and county governments have endorsed IHRA, embedding it across federal, state, and local levels. Adoption extends well beyond governments: universities, schools, law enforcement agencies, and major public and private institutions now use IHRA to shape policy, education, and enforcement.

This global reach demonstrates IHRA’s unmatched authority and utility. No other antisemitism definition has achieved comparable legitimacy or practical impact, which is why IHRA stands as the recognized benchmark for identifying and combating antisemitism.

4. It Balances Free Speech and Accountability

Criticism of Israel is legitimate. What IHRA rejects is not dissent but hate: demonization, double standards, and delegitimization. While non-binding, it provides both a trusted policy guide and an educational tool in democracies committed to free expression.

Why it matters: The IHRA antisemitism definition has become the global standard for confronting Jew-hatred with clarity, authority, and action. By combining recognition, guidance, and legitimacy, IHRA ensures societies can expose and combat antisemitism in all its forms.

Alternative Antisemitism Definitions — and Why IHRA Leads

In recent years, rival definitions have been proposed. While often presented as more “nuanced,” they tend to obscure rather than clarify. Unlike the IHRA antisemitism definition, these alternatives lack broad adoption, practical applicability, and the confidence of Jewish communities.

The Nexus Document

Published in 2021 by a U.S.-based group of scholars, the Nexus Document sought to draw sharper lines between criticism of Israel and antisemitism. Yet it overlooks a central reality: anti-Zionism is now one of the most widespread and dangerous forms of Jew-hatred. Its language creates gray zones that bad actors exploit, and even its authors admit it was never designed for legal or policy use.

The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA)

Also released in 2021, the JDA was drafted by European and American academics as an alternative to IHRA. It sets out 15 “guidelines” but downplays anti-Zionism, introduces ambiguity where clarity is most needed, and privileges academic nuance over Jewish lived experience. Unsurprisingly, it has seen very limited institutional adoption.

Other Attempts at Establishing Defining Antisemitism

Beyond Nexus and JDA, additional efforts exist — such as the Livingstone Formulation, the AzAs (Anti-Zionist Antisemitism) Scale, and various university definitions. While some provide useful insights, they remain too narrow, too academic, or too fragmented to serve as global standards. Together, these alternatives highlight why the IHRA antisemitism definition endures as the only framework that combines clarity, legitimacy, and practical utility — making it the benchmark for governments and institutions worldwide.

IHRA’s Critics

Criticism of IHRA comes from opposite directions. Some argue it goes too far, blurring the line between anti-Israel rhetoric and antisemitism. Others insist it does not go far enough, pointing to its limits in capturing coded online hate or new extremist ideologies. Because the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism is non-binding, some institutions adopt it symbolically but fail to apply it. Yet this very dual critique underscores its unique status: challenged from all sides, but still the most widely endorsed and operationally effective framework in the world.

Why IHRA Remains the Global Benchmark

Adopted by consensus in 2016 by all 34 member states of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism is unique in both clarity and reach. It reflects broad consultation with Jewish communities, civil society leaders, and human rights experts, making it the first antisemitism definition to achieve true international legitimacy.

What sets IHRA apart is not only its precision but its proven impact. From law enforcement training and university policy to government legislation and online platform standards, IHRA has become the standard governments and institutions now rely on. It explicitly affirms that criticism of Israeli policies is legitimate, while drawing the line at demonization, double standards, and delegitimization. That balance is why the IHRA antisemitism definition endures as the most effective and widely adopted tool for identifying, confronting, and reducing antisemitism across borders and institutions.

Measuring, Preventing, and Responding to Antisemitism

Understanding the antisemitism definition is only the first step. Real progress requires turning clarity into action. The IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism provides a universal benchmark for how institutions can measure, prevent, and respond to Jew-hatred.

1. Measuring Antisemitism

A shared benchmark enables consistent, reliable data collection across borders and sectors. Aligning monitoring efforts to the IHRA antisemitism definition allows governments, NGOs, and law enforcement to:

- Identify patterns and trends over time

- Target interventions based on evidence

- Coordinate across jurisdictions

- Protect Jewish communities more effectively

Without this alignment, reports remain fragmented. With it, data becomes a tool for decisive action.

2. Preventing Antisemitism

Prevention begins with education. Institutions can use IHRA to:

- Integrate antisemitism awareness into DEI and HR training

- Embed IHRA-based modules in schools and civic education

- Train educators, journalists, moderators, and police with real-world examples

Clarity equips people to recognize antisemitism before it takes root and spreads.

3. Responding to Antisemitism

When incidents occur, clear standards make accountability possible. With IHRA in place, organizations can:

- Assess complaints consistently and fairly

- Apply sanctions aligned with anti-hate policies

- Support victims and communicate responses transparently

In practice, this means governments writing IHRA into hate-crime legislation, universities enforcing protections for Jewish students, and online platforms moderating antisemitic content. An actionable antisemitism definition does more than describe the problem—it provides the tools to stop it.

Why Clarity Matters: A Final Word

Antisemitism thrives in ambiguity. It hides behind euphemisms, cloaks itself in activism, and exploits loopholes where no shared standard exists. Without a clear antisemitism definition, institutions falter, perpetrators evade accountability, and Jewish communities are left exposed.

The IHRA definition changes that. It draws the line between debate and hate, enabling institutions to act with precision instead of hesitation.

Ultimately, IHRA distinguishes between legitimate criticism of a government and the demonization of a people. It provides societies with the clarity needed to respond effectively.

Take Action: Define Antisemitism, Share the Truth, Protect Communities

Adopt the Standard

Encourage your school, workplace, government agency, or nonprofit to formally adopt the IHRA antisemitism definition. Use it to shape codes of conduct, reporting protocols, training programs, and disciplinary policies.

Educate Widely

Share this resource with educators, journalists, policymakers, and civic leaders. Integrate IHRA—and its 11 real-world examples—into curricula, newsroom style guides, DEI programs, and onboarding materials.

Report and Respond

Silence enables hate. Most antisemitic incidents go unreported, leaving Jewish communities vulnerable. To close this gap, CAM created the Report It app—a fast, secure tool to document antisemitic incidents in real time, from graffiti and harassment to threats and violence. Submissions are reviewed and, when appropriate, forwarded to local leaders, law enforcement, media, or community groups for action.

“We are giving every individual a quick, safe, and effective way to shine a light on hate, hold perpetrators accountable, and drive meaningful change,” said CAM CEO Sacha Roytman.

Every report builds a more accurate picture of antisemitism’s reach and strengthens the resources to confront it. Download the Report It app today on the Apple Store or Google Play.

Track and Improve

Accountability requires vigilance. Audit your systems regularly. Align reporting tools, data collection, and interventions with IHRA to ensure smarter prevention, stronger protections, and measurable progress.

A shared antisemitism definition is more than a statement—it is a strategy for survival, truth, and protection. With IHRA, societies can confront denial, close loopholes, and defend Jewish communities worldwide. Without it, antisemitism adapts unchecked.

The choice is clear. The responsibility is ours. Adopt it. Teach it. Apply it. Enforce it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is antisemitism?

Antisemitism is prejudice, hostility, or discrimination against Jews—targeting Jewish individuals, the Jewish people, or the Jewish state—through stereotypes, conspiracy myths, exclusion, or violence. The antisemitism definition includes demonization, double standards, and delegitimization of Jewish self-determination. For readers asking what is antisemitism, the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism provides the clearest and most widely accepted benchmark.

2. Why do we need an antisemitism definition at all? Isn’t hate obvious?

If hate were always obvious, antisemitism would not have survived for centuries. It hides behind politics, slogans, and activism—making a clear antisemitism definition essential. Without that clarity, bad actors exploit ambiguity to attack Jews without consequence, and institutions too often excuse or downplay antisemitism as “just politics.”

3. What makes the IHRA antisemitism definition so effective?

The IHRA antisemitism definition combines clarity with practical examples. Unlike vague alternatives, it shows how Jew-hatred operates today—from conspiracy myths to Holocaust denial to anti-Zionist rhetoric. This is why the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism has become the most widely adopted global standard. For those asking what is antisemitism in practice, IHRA demonstrates how the antisemitism definition translates into recognition and accountability.

4. How has antisemitism changed over time?

It mutates to fit every age: religious charges in the Middle Ages, racial pseudoscience in the 20th century, and anti-Zionism today. The enduring antisemitism meaning is that the target never changes—only the disguise. That is why a clear antisemitism definition is essential. Only the IHRA antisemitism definition keeps pace with these shifting forms while preserving clarity.

5. How can schools or universities apply the IHRA antisemitism definition?

They use the IHRA antisemitism definition to train staff, assess complaints, protect students, and develop fair policies. By distinguishing between academic debate and harassment of Jews, the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism offers clarity without stifling free expression.

6. How do you draw the line between anti-Israel activism and antisemitism?

The line is crossed when activism employs double standards, denies Jewish self-determination, or repeats antisemitic tropes. In those cases, criticism shifts into hate. The antisemitism definition set by IHRA provides a consistent framework to identify when that shift occurs.

7. Does the IHRA antisemitism definition suppress free speech?

No. The IHRA antisemitism definition is non-binding and explicitly protects debate. It only classifies rhetoric as antisemitic when it demonizes Jews, applies double standards, or denies their right to self-determination. In practice, it safeguards robust debate while ensuring hate is exposed for what it is.

8. Why do some groups oppose IHRA?

Some academics argue it blurs the line between political speech and antisemitism. But in practice, most opposition comes from those who want extreme anti-Israel rhetoric shielded from accountability. Their concern is less about free expression than about avoiding consequences for rhetoric that the IHRA antisemitism definition clearly exposes as antisemitism.

9. Who uses the IHRA antisemitism definition, and how?

Today, more than 45 governments, the European Union, and over 1,200 institutions—including universities, law enforcement, and NGOs—rely on the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism. They use it to train staff, shape policy, enforce legislation, and moderate online content. This breadth of adoption confirms its authority as the global antisemitism definition in practice.

10. Can adopting the IHRA antisemitism definition actually reduce antisemitism?

Adoption alone will not end Jew-hatred, but it forces accountability. A shared antisemitism definition educates the public, strengthens enforcement, and prevents institutions from excusing or minimizing hate. Without it, antisemitism festers unchecked. With it, societies are compelled to confront antisemitism directly and consistently.

Further Reading

- IHRA Adoption Tracker

- IHRA Symposium: A Winning Tool

- The IHRA Definition Explained

- IHRA Antisemitism Definition Adoptions Report 2024 (PDF)

- IHRA Antisemitism Definition Adoptions Report 2023 (PDF)

- U.S. States IHRA Adoptions Database

- Fighting Back Against Durban’s Hate With IHRA

- NYC Executive Order Recognizing IHRA

- CAM’s CHII Antisemitic Incidents Classification System

- Natan Sharansky Appointed CAM Advisory Board Chair