|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This analysis was authored by the Antisemitism Research Center (ARC) by CAM:

On May 14, 2025, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez stood before Parliament and accused Israel of being a “genocidal state.”

This was not a gaffe. It was a lie — deliberate, inflammatory, and dangerous.

Just five days later, Sánchez doubled down — calling for Israel’s expulsion from the annual Eurovision song contest and declaring solidarity with “the people of Palestine who are experiencing the injustice of war and bombardment.”

This wasn’t diplomacy. It was demagoguery. And while it may have been aimed at appeasing the far-left flank of Sánchez’s governing coalition, it echoed something older and far more insidious: a pattern in Spanish political life, where antisemitism — once open and unabashed — has been repackaged in the language of human rights and weaponized for political gain.

Spain’s targeting of Israel is only the latest chapter in a much older story. Last June, the Spanish government joined South Africa’s case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) accusing Israel of genocide. Months earlier, Josep Borrell — then serving as the EU’s foreign policy chief and formerly Spain’s foreign minister — repeated the same charge. These acts are not anomalies. They follow a familiar pattern: vilifying Jews, isolating Jews, and scapegoating Jews. In the contemporary context, Israel is not merely a state — it is the Jew. And the hatred once directed at individuals now finds its mark in the Jewish collective.

A History Written in Jewish Blood

To understand the present, we must look to the past. For over 1,500 years, Spain has persecuted its Jewish population with chilling consistency.

In the 7th century, Christian Visigothic rulers forced Jews to convert or face exile. In the 12th-century, under the Muslim Almohad Caliphate, Jews were given a harsher ultimatum: convert to Islam or die. Maimonides fled. Many others didn’t survive.

By the mid-13th century, the Christian Reconquista had reclaimed most of Iberia, placing Jews once again under Christian rule. But rising religious zeal and interfaith tensions laid the groundwork for even greater violence. The pogroms of 1391 devastated Jewish communities across Castile and Aragon — thousands were murdered, and many more were forcibly converted. These mass conversions gave rise to the converso — Jews who had adopted Christianity under duress – triggering a new wave of suspicion. Their faith was doubted, their loyalty questioned, and their presence resented. Over time, conversos were systematically excluded from public life under Limpieza de Sangre, or “Purity of Blood” laws – early racial codes that foreshadowed Nazi legislation centuries later.

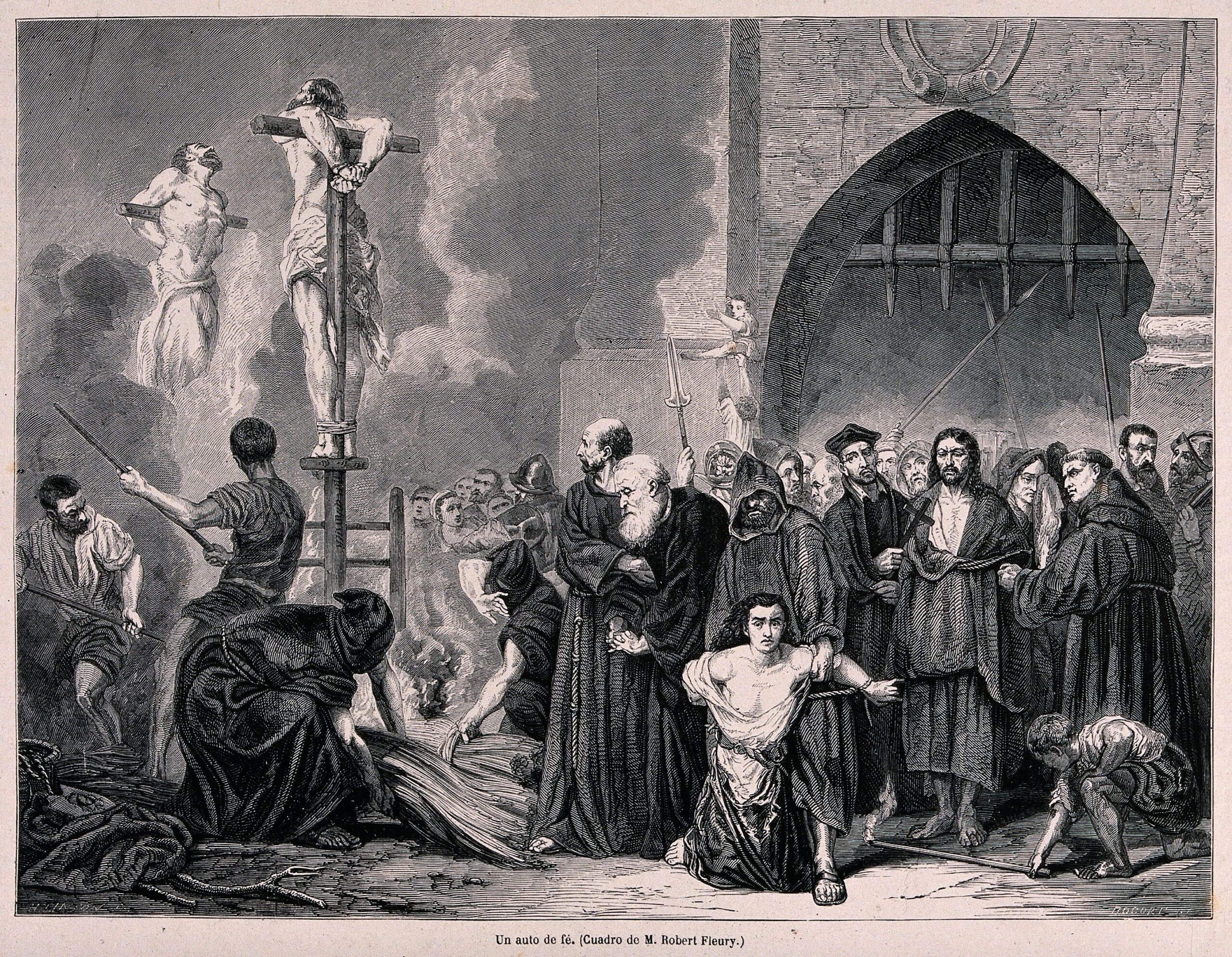

In 1478, Spain institutionalized religious paranoia with the establishment of the Inquisition, targeting marranos – conversos suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. In 1492, Spain expelled all unconverted Jews. While the Inquisition persisted until 1834, the Edict of Expulsion was not formally revoked until 1968.

Under 20th-century fascism, antisemitic conspiracies found new life. As historian Paul Preston documented, antisemitism was central to Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, which ruled Spain from 1939 to 1975. At the heart of his anti-Communist ideology was the “Judeo-Bolshevik” conspiracy theory — an supposed global Jewish plot to subvert society through communist revolution. That rhetoric persists. At a 2021 rally in Madrid, far-right activist Isabel M. Peralta declared: “Zionist and certain strata of that race [Jews] are the people that control the world.”

Even Spain’s geography bears scars of this hatred. In the province of Burgos, the town now known as Castrillo Mota de Judíos — originally recorded in 1035 and meaning “Jew Hill Camp,” a reference to a massacre of Jews in nearby Castrojeriz — was grotesquely renamed Castrillo Matajudios, or “Kill Jews,” in the 17th century. That name remained in place until 2015, when residents finally voted to restore the town’s earlier name.

Given this history, it is no coincidence that today’s political slander targets the world’s only Jewish state — precisely as it defends itself against a genocidal terror group.

Sánchez’s accusation doesn’t break from Spain’s past — it resurrects it.

Antisemitism as Political Currency

Sánchez, leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, has served as Spain’s prime minister since 2018. His latest coalition government, formed in 2023, relies on the support of the far-left Sumar alliance, led by Labor Minister Yolanda Diaz. With a razor-thin three-seat majority in parliament, Sánchez is governing on political quicksand (a majority made possible only through a fragile coalition with Sumar and the backing of several regional parties, including Catalan and Basque pro-independence groups).

That fragility came into sharp focus when Sánchez faced mounting pressure from within his own coalition. In April, Politico revealed that Spain had quietly signed a €6.6 million arms deal to buy ammunition from Israel for its police force — despite Sánchez’s previous pledge to support an arms embargo. The outrage from his coalition partners erupted almost instantly. Diaz — who has repeatedly accused Israel of genocide and publicly proclaimed “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” — demanded the deal be canceled.

Sánchez capitulated. The contract was scrapped — but the political fallout remained. So, under pressure in Parliament, he accused Israel of genocide. Not to promote justice. To protect his government.

The rhetoric that followed was revealing. Gabriel Rufián, a member of Parliament, equated Gaza with Auschwitz and accused Sánchez’s Socialist Party of “trad[ing] with a genocidal state like Israel.” Rather than reject the comparison or defend his government’s integrity, Sánchez leaned into the framing — validating the lie to protect his fragile coalition.

As Holocaust scholar Norman J.W. Goda noted in a February essay, the genocide accusation against Israel is not only false — it’s calculated to provoke. It draws on centuries-old antisemitic tropes, from medieval blood libels to modern-day conspiracy theories claiming Israel controls Western governments and media to manipulate global opinion. In this twisted framing, Jewish survival becomes a moral offense, and self-defense is recast as a crime.

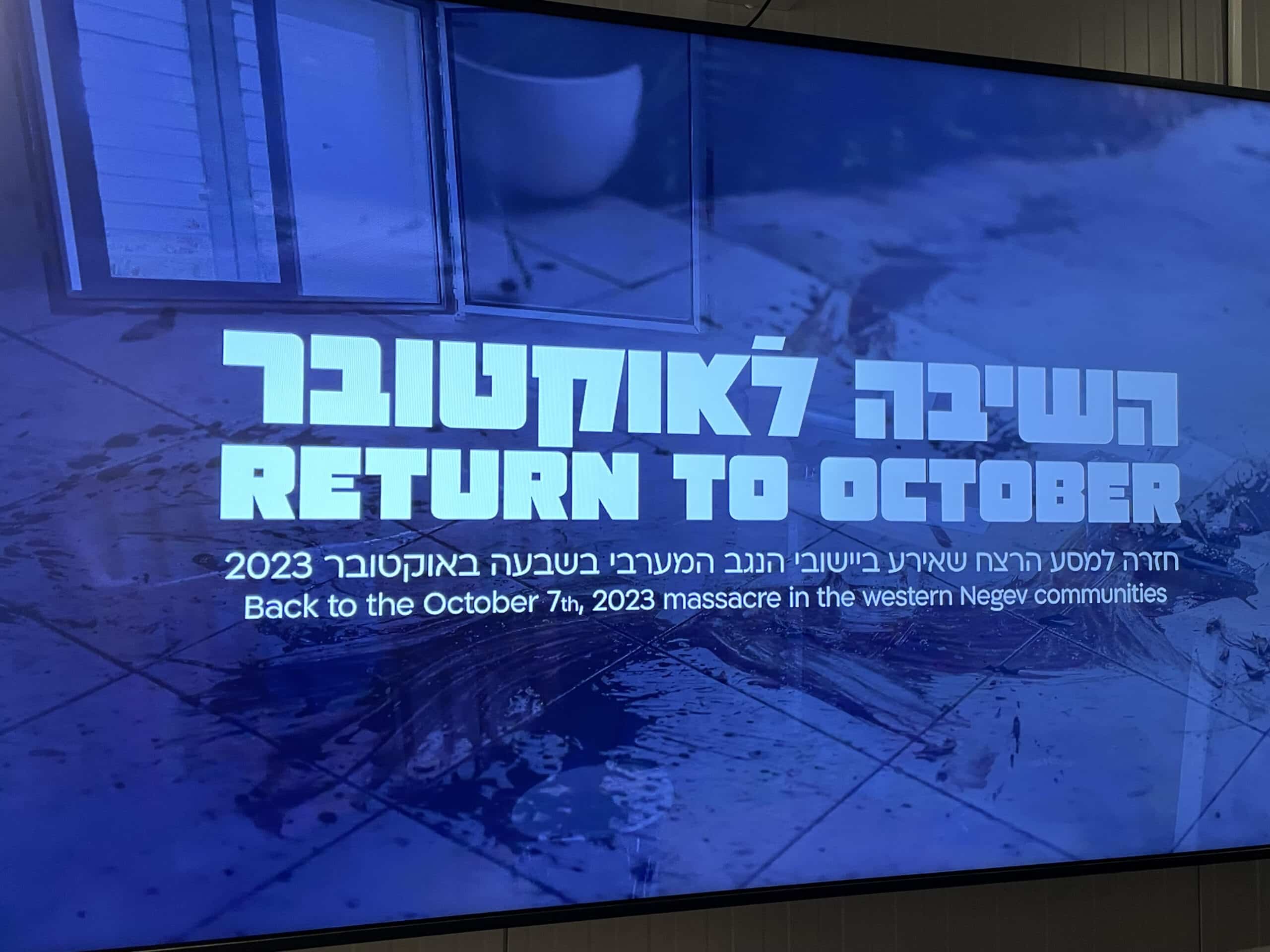

By calling Israel’s war against Hamas — a U.S. and EU-designated terror group that murdered 1,200 people and took 251 hostages on October 7, 2023, in the deadliest single-day massacre of Jews since the Holocaust — an act of genocide, Sánchez did not just malign a sovereign state. He exploited antisemitic tropes to appease his coalition and inflamed hatred that Spain’s Jewish community will be left to bear.

The Fallout of Demonization

The impact was swift — and visible. On May 18, Israeli singer Yuval Raphael competed in the Eurovision finals under threat of violence. Protesters attempted to storm the stage twice. Spanish and Belgian broadcasters aired hostile commentary targeting her performance. Raphael placed second. Two days later, in the name of “solidarity with the Palestinian people,” Sánchez again called for Israel’s expulsion from Eurovision.

Elsewhere, in Bilbao, supporters of the UK’s Tottenham Hotspur — a club long associated with London’s Jewish community and whose fans have historically been derisively nicknamed “the Yids” — were met with banners declaring: “Zionists, You Aren’t Welcome.” The team was in Spain to face Manchester United in the Europa League final on May 21, turning what should have been a celebration of sport into a platform for targeted hate.

Spain’s Jewish community, already small, is now openly worried. “Antisemitism in Spain has become a game piece between the right and the left,” said Raymond Forado, president of the Jewish community of Barcelona.

He’s right. And it must end.

A National Reckoning

Antisemitism in Spain is not a relic of the past — it is a living force, constantly being reinvented. When a prime minister repeats genocidal blood libels against the world’s only Jewish state, he doesn’t just repeat a lie — he sanctions it.

Spain must now choose: Will it confront this legacy or repeat it? Will it reject antisemitism in all its forms — including the fashionable, weaponized kind cloaked in moral language and aimed at the Jewish state — or continue to indulge it for political gain?

The Jewish people have endured centuries of persecution — and they will continue to do so with resilience and resolve. The question is whether Spanish democracy can withstand the hatred it now enables — whether it has the courage to break from its past, or remain captive to it.

History is watching. And it has seen this before.