|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The charge of deicide is the accusation that Jews, as a people, killed Jesus Christ. Although the crucifixion occurred within a specific first-century Roman imperial context, Christian theology gradually transformed that historical event into a permanent moral indictment of an entire people.

For centuries, it shaped how Christian societies across Europe perceived Jews. By assigning collective and inherited guilt, the deicide accusation became one of the most powerful theological foundations of antisemitism. As a result, it normalized exclusion, discrimination, and violence against Jewish communities.

Importantly, Holocaust historians emphasize that antisemitism did not suddenly emerge in the modern era. Long before racial theories developed, religiously-grounded hostility toward Jews conditioned societies to view Jews as morally suspect and blameworthy. Consequently, persecution often appeared justified or even necessary.

From Historical Event to Inherited Guilt

Roman authorities carried out the execution of Jesus using crucifixion, a method of punishment reserved by the Roman state. At the same time, New Testament texts reflect the internal religious and political conflicts of the first century, including disputes between early Christians and certain Jewish authorities of that period.

Over time, however, later interpreters increasingly detached these texts from their historical context. Responsibility shifted from specific individuals in a specific moment to Jews as an entire people, and from a single event to a permanent condition.

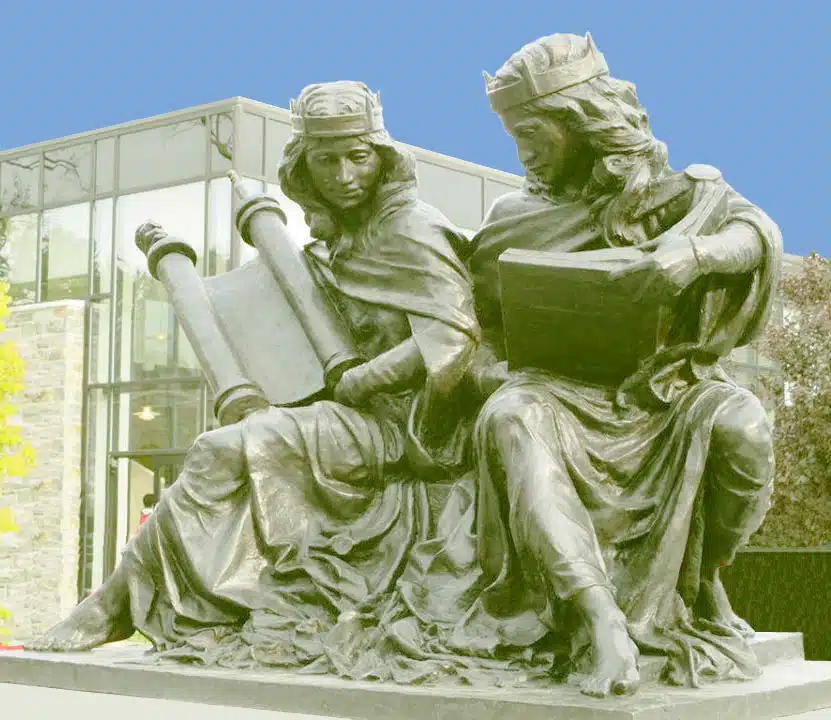

This transformation was deliberate and consequential. It allowed Christian societies to treat Jews as a people marked by guilt regardless of time, place, or conduct. By the medieval period, preaching, Passion narratives, religious art, and popular devotion had embedded the idea of collective Jewish responsibility for Christ’s death. Consequently, these narratives shaped social attitudes toward Jewish communities throughout Europe.

Why the Deicide Charge Is Inherently Antisemitic

The deicide accusation is antisemitic because it does not judge individual actions. Instead, it assigns collective and inherited guilt, transforming Jewish identity itself into a moral offense.

Once guilt becomes inherited, Jews no longer need to face accusations for present actions. Instead, condemnation precedes any conduct. When societies accept collective guilt, they eventually imagine collective punishment as legitimate.

Words as Permission: How Theology Enabled Violence

The most dangerous feature of the deicide charge was not its claim about the past, but its function in the present. By portraying Jews as “Christ-killers,” Christian societies acquired a moral framework that justified humiliation, forced conversion, expulsion, pogroms, and violence. In this framework, hostility appeared as piety, while punishment masqueraded as correction.

Holocaust education institutions have documented that antisemitism often operates through long-term discrimination punctuated by outbreaks of violence. Crucially, religious narratives portraying Jews as deserving of punishment helped sustain this pattern over centuries.

The Jewish Experience of Inherited Accusation

For Jewish communities, the charge of deicide meant living under permanent suspicion. Society judged Jews not by actions or beliefs, but by an accusation attached to their very existence.

This inherited blame justified social exclusion, legal restrictions, and episodic violence. Moreover, it portrayed Jews as morally culpable before any interaction occurred. As a result, Jewish life lost moral neutrality, and Jewish presence itself appeared suspect.

The accusation therefore did more than distort Christian theology. It shaped the lived reality of Jewish life in Europe for centuries.

Formal Repudiation in the Post-Holocaust Era

The devastation of the Holocaust forced institutions across Europe to confront the moral consequences of inherited antisemitic ideas. Within the Catholic Church, this reckoning culminated in Nostra Aetate (1965). The declaration explicitly rejected assigning collective responsibility to Jews for the death of Jesus and warned against portraying Jews as rejected or accursed by God. This shift dismantled the theological logic that had sustained the deicide accusation for centuries.

Reinforcement in the Catechism

The Catechism of the Catholic Church reinforces this rejection with explicit clarity. It affirms that Jews do not bear collective responsibility for Jesus’ death and rejects any attempt to transform the Passion into a collective indictment. Because religious instruction transmits ideas across generations, this clarity plays a critical role. By removing ambiguity at the catechetical level, the Church reduced the likelihood that antisemitic myths would reemerge.

Why Repudiation Required Ongoing Education

Church leadership understood that formal rejection alone would not suffice. Accordingly, in 1974, the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews issued Guidelines and Suggestions for Implementing the Conciliar Declaration Nostra Aetate (n. 4). These guidelines called for reform in preaching, education, and biblical interpretation.

Later, in 1985, the Commission released Notes on the Correct Way to Present the Jews and Judaism in Preaching and Catechesis. This document explicitly warned against stereotypes, prejudice, and the reintroduction of offensive narratives.

Together, these texts reflect a clear institutional recognition that theological reform requires sustained vigilance. Without it, inherited narratives easily return through habit and tradition.

Despite formal repudiation, the deicide accusation has not disappeared. Instead, it continues to surface in extremist rhetoric and antisemitic discourse because of its historical power. Its persistence reveals a broader truth. Antisemitism survives not only through falsehoods, but through narratives that make collective blame feel intuitive and morally justified.

The Historical Lesson

The charge of deicide demonstrates how a theological idea can shape social reality. It shows how societies normalize inherited guilt, how moral language becomes weaponized, and how persecution appears righteous. When societies accept collective guilt, they eventually accept collective punishment.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the charge of deicide?

The charge of deicide is the antisemitic accusation that Jews collectively killed Jesus Christ and therefore bear inherited and permanent guilt.

Is the charge of deicide historically accurate?

No. Roman authorities executed Jesus in a first-century imperial context. The deicide charge transforms a historical event into a collective moral indictment unrelated to historical responsibility.

Why is the deicide accusation considered antisemitic?

Because it assigns collective and inherited blame to Jews as a people, turning Jewish identity itself into a moral offense.

Did Christian teaching historically promote the charge of deicide?

Yes. For centuries, Christian preaching, art, and popular theology promoted or tolerated the idea of collective Jewish responsibility for Jesus’ death, shaping antisemitic attitudes and persecution.

Did the Catholic Church reject the charge of deicide?

Yes. In Nostra Aetate (1965), the Catholic Church explicitly rejected assigning collective responsibility to Jews for Jesus’ death.

What does the Catechism of the Catholic Church say about responsibility for Jesus’ death?

The Catechism states that Jews are not collectively responsible and that responsibility for Christ’s suffering cannot be assigned to a single people.

Did the charge of deicide contribute to violence against Jews?

Yes. The accusation helped justify centuries of discrimination, forced conversion, exclusion, and violence by portraying Jews as permanently guilty.

Does the deicide myth still appear today?

Yes. Despite formal repudiation, it continues to surface in antisemitic rhetoric and extremist ideology due to its deep historical roots.