Italy’s National Coordinator Against Anti-Semitism Calls For Renewed Commitment By Whole of Italian Society

In January 2020, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte appointed Professor Milena Santerini as the first-ever National Coordinator for the Fight Against Anti-Semitism, joining the European Union, Germany and the United Kingdom in appointing a senior official to coordinate strategy against the rise of anti-Semitism across Europe.

Ms. Santerini is a member of the culture, education and sports commission of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Italian parliament, and also serves as a delegate to the Council of Europe in the equality and non-discrimination commission. She teaches pedagogy at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan and is also the vice-president of the Shoah Memorial Foundation in Milan and member of the National Didactic Council of the Museum of the Shoah Foundation in Rome.

The Italian Jewish community, – neither Ashkenazi or Sephardic – and one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities, has praised Ms. Santerini’s appointment and her subsequent work tackling anti-Semitism. As Ms. Santerini’s first year as National Coordinator for the Fight Against Anti-Semitism comes to a close, Tamara Berens of the Combat Anti-Semitism Movement (CAM) spoke with her to discuss the phenomenon of contemporary anti-Semitism in Italy and her office’s new national strategy to combat anti-Semitism throughout Italian society.

What motivated you to get involved with Holocaust remembrance?

Throughout my life I have always been aware that the memory of the Shoah is universal: a fundamental watershed in contemporary European history. Since the 1990s I have been teaching about the Holocaust in schools, training teachers and students to ask themselves moral questions about the deportation of the Jews of Europe and the events of the Holocaust. My books on anti-Semitism and the cultural initiatives of those years followed from my early experience.

In particular, I developed friendships with Milanese survivors: Liliana Segre, Goti Bauer, and Nedo Fiano [prominent Auschwitz survivors and public speakers in Italy]. In 1997, I began commemoration ceremonies with the Community of Sant’Egidio and the Jewish Community in Milan to remember the deportation of Liliana Segre, on January 30, 1945, from the basement of Milan’s Central Station.

Those annual ceremonies gave rise to the idea of creating a Holocaust Memorial in those places, of which I am today Vice President. As a delegate to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) I have followed issues relating to the transmission of Holocaust memory in Italy. I firmly believe that both the trivialization and the “sacralization” of memory must be avoided. It is important to remember that we are not only talking about figures, places, and dates, but about people’s life stories, and about the mechanisms that still create prejudice, discrimination, and hatred.

Can you describe some of the ways that anti-Semitism has resurfaced in Italy in the decades since the Holocaust?

At first, when Holocaust survivors returned from the camps, many ignored their testimony. For example, Primo Levi’s book “If This is a Man”, published in 1947, remained unknown and was only reprinted in Italy in 1958. In the mid-1950s, Nazi crimes were not yet strongly denounced because of the Cold War. Rather than Jewish memory, we commemorated the politically motivated deportations. In 1968, remembrance became universal as the new generations demanded an end to discrimination and racism.

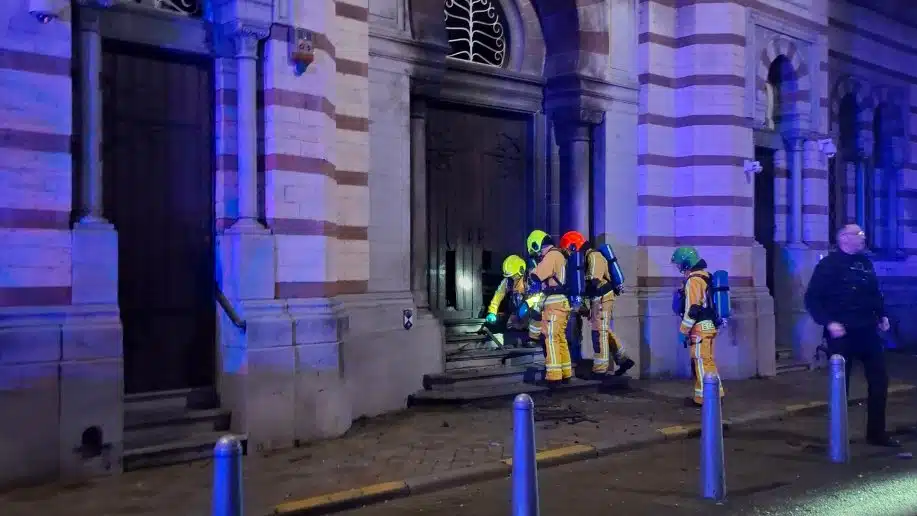

Anti-Semitism remained rooted in Italian society after the war and never disappeared. But it went through a particular resurgence in the 1980s both in the form of right-wing extremism from neo-Nazi groups and from those who were hostile towards Israel. This problem was epitomized by the terrorist attack on the Great Synagogue in Rome on October 9, 1982. Anti-Semitism becomes more prominent as time marches on since the events of the Second World War. It is also influenced by the different phases of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

A landmark study in 2015 published by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research found that almost 70% of Italian Jews reported a rise in anti-Semitism. In your opinion, has anti-Semitism in Italy become more or less prevalent in the last 5 years since the study?

In Italy, the perception of this danger on the part of Jews has grown and the number of Italians (58%) who think that the problem of anti-Semitism is very (16%) or quite important (42%) has increased, too (Eurobarometer 2019).

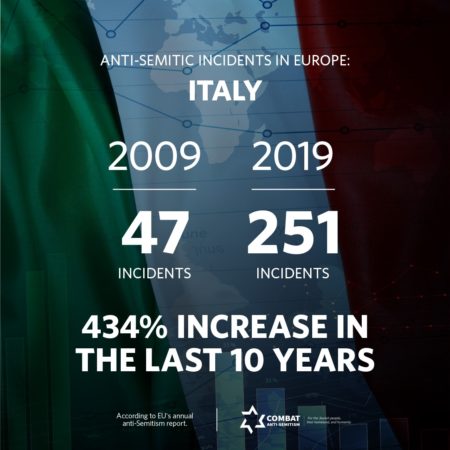

In 2019, the CDEC’s Anti-Semitism Observatory recorded 251 episodes of anti-Semitism, significantly more than in 2018 (197) and 2017 (130). Most of these are online. Broadly, the phenomenon of anti-Semitism and is increasing, and incidents are more visible. The peak in anti-Semitic incidents occurred in 2019 when Liliana Segre was subjected to verbal harassment online.

However, it is not easy to confirm a quantitative increase of anti-Semitism in absolute terms because anti-Semitism today does not present itself solely in the traditional forms of Christian anti-Judaism and biological racism.

Nazi-Fascist anti-Semitism has resurfaced in the current extreme right-wing formations that commit hate crimes using symbols and images typical of Nazi propaganda, which directly or indirectly endorse fascism. Among the new forms of anti-Semitism, there is a widespread hatred of Israel. The country is demonized and equivocated with Nazism. Some continue to attribute the misfortunes of humanity to a central agent: yesterday it was “the Jew,” today, “Israel.”

The myth of the global Jewish conspiracy and its financial, economic, and media power is still very much present in Italian society and in some left-wing groups.

How has the global pandemic affected anti-Semitism in Italy?

During collective traumas, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, ancient conspiratorial myths re-emerge. For example, many blame the Jews for spreading the virus (like the poisoning of wells in the Middle Ages). Another accusation has to do with blood (the Jews who allegedly use the blood of Christians for their rites), now transposed into online myths (for example: QAnon, now also in Italy).

Even if hatred during the pandemic in Italy was mainly directed against the Chinese, there were also expressions of anti-Semitism that blamed the Jews for various factors such as conspiracy to infect, economic exploitation of the virus, and so on.

Links made between the pandemic and Jewish people reveals the total nonsensical nature of anti-Semitism. An analysis of anti-Semitism on Twitter from March-May 2020 carried out by the Catholic University’s Mediavox Observatory during the pandemic shows two prevailing positions: anti-Semitic hatred attributed to conceptions of Jewish power and to the demonization of Israel. Generally speaking, a climate of anxiety and economic uncertainty can contribute to the growth of anti-Semitic prejudice in the population that elects Jews as a “target group.”

How should European states combat online hatred towards the Jewish people on social media?

Defending freedom of expression at all costs has thus far been the favored approach of social media platforms and search engines (Facebook, Twitter, Google, Instagram, YouTube and others), although this position is slowly changing. Recently, some interventions by Twitter or Facebook, for example against Holocaust denial, suggests a policy shift.

Until now, a certain inertia has prevailed, both because of the Web’s vision as a “paradise of democracy”, and because of the political action and economic interests of platforms that avoid being held to account for their content. The result has been that discriminatory and offensive content inciting hatred in ways that would be sanctioned in traditional media are spread instead on social networks, and risk going unpunished. Procedures for reporting and removing abusive content often prove inadequate.

Interventions are needed to counter everyday hatred, expressed by organized groups or otherwise, which poisons the infosphere. We should encourage greater cooperation with the European Code of Conduct to fight against illegal forms of incitement to online hatred.

In order to prevent hate messages from “going viral” in light of the difficult boundary between legitimate expression and discriminatory speech, the detection and identification of hate content by research institutions and universities should also be encouraged. Nonetheless, this is very difficult both because of the endless mass of messages exchanged every day and because of limitations in the use of algorithms to identify hate speech.

You began your post as national coordinator in January. What are your goals for this position? What would you like to achieve or change on a societal and governmental level?

After being appointed National Coordinator for the fight against anti-Semitism at the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, I set up a working group to conduct a survey on the application of the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism. This group is made up of representatives of the Jewish communities, ministries, and experts. We are preparing a Final Report with the Italian National Strategy on Anti-Semitism. We ask the Government and the Parliament to intervene and identify anti-Semitism specifically among other hate crimes. Particular attention should be paid to fascism and Nazism that re-emerges in “casual” forms. It is important to improve data collection by judicial authorities and the police to distinguish anti-Semitism from other hate crimes.

In the world of education and culture, and for those who train teachers, the judiciary, and media workers, we will update perceptions of anti-Semitism, taking into account its new forms observed in recent years, such as the demonization of Israel and new conspiracies, and especially the characteristics that anti-Semitic hatred acquires online. Here, we ask for national legislation forcing social media companies to remove hate speech from their platforms. We must also step in and demand a more rigorous approach to fighting anti-Semitism and racism in the world of soccer.

In short, we call for a new and renewed commitment against anti-Semitism by the whole of Italian society.